[Above, a placard demonstrating that feminist memes are about as apt and witty as they are grammatical.]

Feminist uproar over Trump’s election was easy to predict, and not long in coming. Within ten days of the election, Clara Jeffery wrote in Mother Jones that “Women are furious—in a Greek mythology sort of way.” Taking examples from TikTok, Jeffery chronicled abundant “sorrow and disbelief and terror, but also incandescent rage,” which many women vowed to exorcise on men: “‘If his ballot was red, his balls stay blue,’” she quoted one.

In The New York Times, a 16-year-old girl, Naomi Beinart, charted her tumultuous emotions, which included a sense of betrayal because her male classmates had carried on with their lives on the day after the election, seemingly immune to the girls’ all-pervasive gloom and outrage. “Many of them didn’t seem to share our rage, our fear, our despair. We don’t even share the same future,” Beinart opined melodramatically.

No one with even a minimal acquaintance with social media can have missed the many similar, raging reactions: the heads being shaved, the death threats, the promised sex strikes, the fantasies of revenge against Trump-voting husbands. We are to understand that the re-election of a man rumored to lack sufficient pro-abortion commitment justifies thousands of self-recorded screams, imprecations, and poisoning plots.

At least one group of women gathered physically in Wisconsin to shout their angst and anger at Lake Michigan, and there have already been tentative (though apparently less enthusiastic than formerly) plans for a revival of the anti-Trump Women’s March protests, in which women with vulgar placards and pink hats exhibited their “collective rage.”

Women’s rage is all the rage.

**

It is not enough, it seems, for these women to say that they are disappointed by Trump’s win, and certainly inadequate for them to state strong disagreement with his policies or style. Expressing evidence-based positions is the sort of thing a rational person would do, and significant groups of women appear increasingly uninterested in rational talk or behavior. Instead, they reach for the most extreme language, tone of voice, postures and actions to express what feminist journalist Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett called the “visceral” “body horror” produced by the Trump victory, including the “profound physical revulsion” Cosslett and many of her sisters allegedly feel simply as a result of seeing one of Trump’s tweets (talk about fragility!).

Like so many feminist pundits telling us of women’s “horror” and “fury,” the emphasis is squarely on feeling and the female body, as if to bypass the intellect and the will altogether. The idea some feminists once scorned—that women are less reasonable and self-controlled than men—seems to have become a feminist axiom.

No one imagines that if Kamala Harris had won the election, men would have been recording themselves bellowing at a lake or elaborately “joking” about poisoning their Democrat-voting wives. Nothing but incredulous laughter, and perhaps visits from the FBI, would have greeted such over-sized self-pity and maniacal revenge-seeking. Ah, but men’s reproductive rights weren’t at risk in the election, a feminist will say.

True enough. Men lost their reproductive rights long ago, and nobody has ever seriously thought the loss could become an election issue. A woman can put a pin in a condom (or collect sperm from a discarded one) and force the unsuspecting man to pay support for a child he never intended to father and whom he likely won’t be allowed to parent at all. Many men end up financially supporting children who aren’t even theirs as a result of a paternity fraud colluded in by state governments. Worst of all, men can and do regularly have their children judicially stolen from them, as Stephen Baskerville has eloquently explained. If such things were occurring to tens of thousands of women in the United States every year, as they are to tens of thousands of men, women would be screaming about that too—because that’s what women do.

Women’s rage at Trump’s win isn’t about Trump; it’s about rage.

**

Rage is a common emotional state for many women today as well as a normalized political posture, and many feminists are happy to say so. In 2018, feminist academic Mary Valentis, revisiting her 1994 book on the subject (Female Rage: Unlocking Its Secrets, Claiming Its Power), observed that female rage, which she lauded as an “often demonized but ultimately empowering force,” had been surging for at least the previous quarter century, spurred by “such celebrated cases as Anita Hill and Clarence Thomas, the breakup of Princess Diana and Prince Charles’ marriage, and films like Fatal Attraction.” (As I will show below, it has been roiling for much longer than that.)

What was the fuss about Princess Diana or the Michael Douglas thriller? If those particular stories have faded from view, it doesn’t matter: rage always finds fuel. Surveying the feminist landscape in late 2018, and expressing particular satisfaction at the success of the MeToo movement, Valentis applauded the many angry women who were “recognizing the strength in shared experience.”

Far from being forbidden or frowned-upon, women’s rage is now widely justified by a panoply of experts and opinion-makers. In an article for feminist journal Refinery29 (“Rage Becomes Her”), Natalie Gil was adamant that women’s anger was a potent political force that should be made more public and visible. Craig Mattson (“Why You Should Feel Rage at Work”) validated fury in the workplace, finding “something honest and vital about systemic wrath,” and encouraging “simmering rage” so long as it was in “opposition to gender-based, sex-based, race-based discrimination.”

There is now a widely touted phenomenon known as “rage cleaning,” in which put-upon housewives slam down the toilet seat and then fake-apologize for startling the oblivious men in their households. A whole new genre of books and psychology articles details “mom rage,” which includes fury at imputed male freedoms and resentment at children’s demands. One raging woman admitted to wanting to punish her husband for, allegedly, “getting to do whatever the f__ he wants” while she felt shackled to their kids.

Simply thinking over the unfairness of being female can apparently set off apoplexy: college student Alicia Alvarez wrote for her campus newspaper that “I become cold and detached as I explain all of the injustices done to me personally, and to those who identify as women.” She defined “feminine rage” as “an ancestral and inherited response to the struggles, oppressions, and wrongdoings that women have been subjected to,” and encouraged her generation of young women to give it voice.

The once-common recognition that rage is destructive, a sign of immaturity or irrationality, seems to have been thoroughly rejected.

No wonder there is a reported “gender rage gap.” Feminist journalist Arwa Mahdawi (“A widening gender rage gap”) pointed out in 2022 that ten years of Gallup polling showed women around the world “consistently report[ing] feeling negative emotions more than men.” For Mahdawi, such findings were easy to explain: “There is a lot for women to be angry about.”

She too, of course, repeated the standard line about women’s anger. “Men have always been allowed to lose their cool; women, particularly minorities, get punished for it.” (Nonsense! Our societies mistrust and rebuke men who cannot control their emotions.) For Mahdawi, it was time to “embrace the fact that women are getting angrier” because such anger can be “a powerful catalyst for change.”

Perhaps it can. It can also do a lot of damage.

**

Mahdawi and many other commentators assume as a matter of course that female rage is a response to unjust suffering. Women are angry because they have been wronged. While such is an understandable assumption, it is not necessarily correct. Rage can also be a learned behavior or even a calculated performance: exhilarating and manipulative, punitive and self-authored.

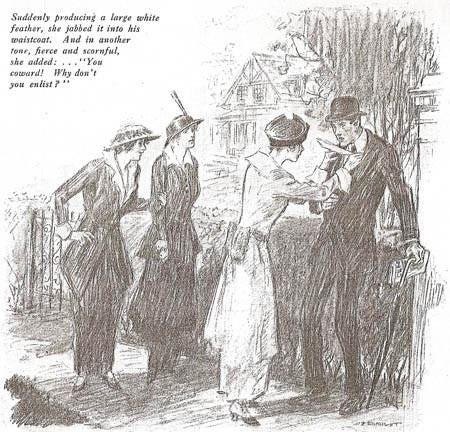

Let’s consider a historical example of rage and suffering during the First World War, when thousands of British women participated in a mass shaming ritual to coerce men to enlist in the war against Germany and its allies. Women across Britain in the thousands and possibly tens of thousands, as estimated by researcher Will Ellsworth- Jones (the exact number is unknown), organized themselves into White Feather Brigades to accost men and boys in civilian clothes, handing them white feathers as symbols of cowardice and making clear their furious contempt (for a scrupulously researched if somewhat feminist-compliant account, see Nicoletta Gullace’s “White Feathers and Wounded Men”).

The women’s campaign of public scorn, which sent many men to horrific deaths, went on for the entirety of the war’s four and a half years, long after the British government introduced conscription in 1916. The fact that women continued to hand out feathers years after there was any plausible justification—right up until the end of the war, when its horrors were well known and men with limbs blown off were a common sight on British streets—suggests that more than patriotism was involved. Many women acted with heartless abandon, giving the feathers to wounded men on leave and even under-age boys.

What motivated these women to send so many men and boys to the hell of war? No one is now sure. Times correspondent Michael MacDonagh (who kept a wartime diary later published as a book) described the look of disgust on three women’s faces as they presented feathers to two young men in a London tramcar. “Why don’t you fellows enlist? Your King and Country want you. We don’t,” he recorded their words. Gullace quotes a woman who said she was “very angry” at men she perceived to be shirking their duty.

For Gullace, women’s participation in the White Feather campaign was part of a wartime enactment of ideals of masculine courage and feminine moral power. Historian Peter J. Hart alleged that the campaign gratified the women who participated because it “allowed them to gain power over the men who usually ruled them.” Researcher Robin Mac Donald (“White Feather Feminism: The Recalcitrant Progeny of Radical Suffragism and Conservative Pro-War Britain”) took this view further, emphasizing the overlap in membership between the pre-war militant suffragettes who smashed shop windows and put bombs in letter boxes, and those women who later joined the White Feather movement; he argued that the two very different campaigns had similar roots in female rage, with both designed to legitimize and mobilize anti-male fury.

Not all men wanted to go to the front, of course, and some could not forget the role that their countrywomen had played in harassing them. One man, G. Backhaus, told of a sixteen-year-old cousin who was so traumatized by repeated taunts of cowardice from white feather women that he lied about his age in order to get to the front, and was promptly killed there. The “cruelty of the White Feather business,” Backhaus declared long afterwards, deserved to be exposed. At the time, most men accepted the situation. Times correspondent MacDonagh recorded one example of male restraint in his diary:

A gallant young officer was recently decorated with the V.C. [Victoria Cross, highest honor for courage] by the King at Buckingham Palace. Later on the same day he changed into mufti and was sitting smoking a cigarette in Hyde Park when girls came up to him and jeeringly handed him a white feather… . He accepted the feather without a word and, as a curiosity, put it with his V.C. It is said he remarked to a friend that he was probably the only man who ever received on the same day the two outstanding emblems of bravery and cowardice. Within a week he had returned to the front and made the Great Sacrifice (qtd. in Gullace).

**

It’s impossible to believe that women’s lack of the vote, at a time when not all British men had the vote, was a more outrageous experience of injustice than being sent to die in the fields of Europe—as about 850,000 British men were during that war, while many more survived with terrible wounds, trauma, and amputations. Few women spoke afterwards of what had caused their heartless gusto. The White Feather movement strongly suggests that women’s rage against men is not necessarily a result of female suffering. It may be, on the contrary, a fact of female nature that some women indulge and exploit.

Then as now, horrific suffering was an accepted part of men’s lives, and little attention would be paid to any man who raged against it.

Women’s rage, on the other hand, usually inspires concern and sympathetic response, and feminist leaders have historically affirmed and stoked it. From the beginning, such leaders encouraged women to believe themselves deeply wronged by men and justified in accusing, blaming, and vilifying them. Consider the following:

Feminist leaders have consistently lied to women about their history, as, for example, Elizabeth Cady Stanton did in her inaugural Declaration of Sentiments (1848), an aggressive list of women’s grievances and demands from the first women’s rights conference, which included the apocalyptic accusation that “The history of mankind is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man towards woman, having in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over her.”

Feminists have incited women to reckless violence, as Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughter Christabel did in the years of (now little-known) suffragette terrorism before the First World War, when thousands of maddened activists set off bombs, burned country houses to the ground, and attempted to assassinate politicians in response to Emmeline Pankhurst’s 1913 contention that “the time [was] long past when it became necessary for women to revolt in order to maintain their self-respect” (“Why We Are Militant,” in Suffrage and the Pankhursts).

Feminists have taught women to see male pain and death as, in a sense, deserved or at least not worth mourning—allegedly because other men caused it, or because men were complicit in women’s greater suffering—as feminists did, for example, following the sinking of the Titanic in 1912, when Alice Stone Blackwell, editor of the suffrage publication Woman’s Journal, refused to acknowledge men’s sacrifice, alleging that “There was no need that a single life should have been lost upon the Titanic,” and claiming “There will be far fewer lost by preventable accidents, either on land or sea, when the mothers of men have the right to vote” (qtd. in Steven Biel, Down With the Old Canoe: A Cultural History of the Titanic Disaster, p. 105; many other examples are to be found here).

Feminists have depicted women’s daily lives as grotesquely deformed by sex-based injustice, confinement, drudgery, and abuse, as did Simone De Beauvoir in her 1949 chronicle of the process of “becoming” woman—the “[w]ashing, ironing, sweeping, routing out of tufts of dust in the dark places behind the wardrobe”—to which one must “submit […] in rage” (The Second Sex, p. 450). Beauvoir’s myth-making was recast and updated for an American audience in Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (1963), in which post-war suburban life for women was described as a “comfortable concentration camp” involving “a slow death of mind and spirit” (p. 369).

Andrea Dworkin claimed in a 1983 speech that all women suffered under patriarchy: “We are very close to death. All women are. And we are very close to rape and we are very close to beating. And we are inside a system of humiliation from which there is no escape for us.” The primary point in these and many other such feminist proclamations was that female rage was inevitable, necessary, liberating, and good. As Robin Morgan explained at the beginning of her 1974 essay “International Feminism,” “To be female and conscious anywhere on this planet is to be in a continual state of rage” (Going Too Far, p. 248).

The implication, clearly, was that not to be in a continual state of rage was to be unconscious, indifferent, and a traitor to women and oneself.

**

As such effusions indicate, there is nothing new—and certainly nothing long-suppressed or overdue, nothing organic or spontaneous—about the wrath-filled venting and furious execrations that have greeted Trump’s victory. They are utterly predictable and de rigueur, part of an assiduously-curated political program that teaches women to be their worst—their least rational and trustworthy, most destructive and unaccountable—selves.

The final word on such designer rage, and perhaps the clearest symbol of why anyone who encourages it should be shunned, belongs to feminist author Mona Eltahawy, who proposed a few years back that young girls should be explicitly taught to augment and unleash their rage. Predictably, Eltahawy begged the question by calling such rage a “justified and righteous reaction to injustice.” In her 2018 essay “What the world would look like if we taught girls to rage” (which in fact offered no realistic picture), Eltahawy enthused about a teaching curriculum on “Rage for Girls,” which would fill them with fury at all the wrongs allegedly done to their sex.

Surely her own work would figure prominently in such a curriculum: Eltahawy published The Seven Necessary Sins for Women and Girls in 2019, with a chapter each on anger and violence. An unabashed proponent of anti-male violence, she has boasted about beating a man who groped her in a Montreal nightclub and fantasized about vigilante killings of men, wondering “How many men must we kill until patriarchy sits across the table from us and says, ‘Ok, stop.’”

“I want to bottle-feed rage to every baby girl so that it fortifies her bones and muscles,” she gushed risibly in the afore-mentioned essay. “I want her to flex, and feel the power growing inside her as she herself grows from a child into a young woman.” Alleging that girls were wrongly “taught” at a young age to feel “vulnerable and weak” (denial of biological reality always a central plank of feminism), Eltahawy ended the essay by asserting that “Angry women are free women.”

**

Wrong.

Rage is exhausting and sick-making, not freeing. It clouds judgement and extinguishes empathy, muting joy and warping perception. Though so often touted as a goad to political action (which, admittedly, it can be), it is just as often an end in itself that leaves the enraged person unable to complete projects or maintain relationships. Rarely managing to focus on its putative target, rage almost always expands its domain, bleeding into other areas of life.

Rage is also addictive. Once one is habituated to reciting “all of the injustices done to me personally, and to those who identify as women,” as college student Alicia Alvarez described, the feminist rage-frame comes to seem the only one possible. The experiences that many feminists today find so maddening—many of them related to female psychology and the stresses of adulthood—are not easily resolved and may well be ineradicable. Moreover, the energy and sense of purpose that rage initially provides tend to eclipse other, more modest, states of being, such as gratitude and patience, that are far more conducive to well-being. Girls should be taught to guard against rage, and it should be recognized as one of the most debilitating of female emotional states.

Naturally, women’s rage will generate rage in others—or at least irritation, mistrust, and disgust. Screamed at, discriminated against, bullied, and accused, the targets of feminist rage will turn women’s fury back on them; and will determine, quite reasonably, that raging women have little claim to full citizenship. Rage cannot heal divisions or imagine a just future. Its legacy is resentment, bitterness, and dysfunction.

Ultimately, women’s rage is good for only one thing: maintaining feminism. It makes everyone touched by it—women themselves, their children, and the men who love them—less happy and less able to meet life’s challenges. That rage has become an idol of feminist advocates may be the best evidence for feminism’s bottomless malevolence.

Janice, you just keep hitting it out of the park. Excellent, informative and interesting as all hell. Fantastic article!

I think our ancestors, men and women, were aware of the debilitating levels of negative emotion inherent in many women and ancient societal norms mitigated against it.