Don't Believe that Women Weren't Believed

The historical record shows that over the past century and a half, at least some sexual assault complainants in the Anglophone world garnered both sympathy and belief.

The clear implication of #BelieveWomen is that women weren’t believed in the past.

But is it true?

And what do we mean by the past? Do we mean prior to 2017 and the launching of the #MeToo movement, with its plethora of evidence-free and often anonymous accusations (as, for example, the Shitty Media Men list)?

Or prior to 1991, when Anita Hill’s charges against Clarence Thomas (“Who has put pubic hair on my Coke?”) provoked a nation-wide discussion of workplace sexual harassment, with many proclaiming “I believe Anita Hill.”

Or prior to the 1980s, when Andrea Dworkin and Catharine MacKinnon wrote books and legal articles about sexual coercion as a widespread strategy of male domination?

A considerable number of people, including legal scholars, judges, and victims’ advocates, have been talking about rape in a way that affirmed women’s accounts without question.

What if we go back even earlier, to the early twentieth or even nineteenth centuries? Surely rape complainants weren’t believed then?

Obviously it’s a big question, impossible to answer categorically without a more extensive investigation than can be outlined here. It would take years of combing through primary documents—actual legal cases, and newspaper reports about them—to arrive at anything close to a definitive answer about whether and under what circumstances women were believed. Today it is difficult to rely on secondary sources such as articles and books on social history because nearly all of these are filtered through a feminist lens. Feminist scholars tell us that women were not believed 100 years ago or more, and that very few of the sexual assault cases brought to trial resulted in conviction. But then, that’s exactly what feminist scholars and activists tell us about the situation today. What is the truth?

If we read feminist accounts of rape law in the 19th century, such as Constance Backhouse’s Petticoats and Prejudice: Women and Law in Nineteenth-Century Canada (1991), we notice a few things apart from the insistence that women weren’t believed. We notice, first, that rape was considered a very serious crime, punishable by death in the early 19th century and by life imprisonment from about mid-century onward. Rape and other forms of sexual assault were reported extensively in the newspapers, attracting huge public interest amongst both women and men, often with significant sympathy for rape victims. “Shocking brutality” and “Horrible outrage on a Woman,” shouted the newspapers in 1858, reporting on a gang rape alleged to have occurred in Toronto, Canada (p. 81).

Backhouse spends a good part of a chapter detailing the conduct and outcome of the trial. She notes that the two women alleging the gang rape were unusual complainants in that both were working as prostitutes when the alleged rape occurred, and one had spent time in jail. She describes the witnesses called and the arguments made, and reports that the not guilty verdict for the primary accused was “not atypical” (p. 99). Backhouse’s thesis is that that rape victims rarely found justice. But it is impossible to know if that contention is true, given that she provides no figures for cases and verdicts, or even a range of representative cases.

All that the particular case demonstrates for certain is that even prostitutes were able to take rape cases to court and to find at least some sympathetic interest amongst the newspaper-reading public. Backhouse’s explanation for the low rate of rape convictions is typically feminist, alleging a pro-male bias in the legal system: “Where the struggle was between a woman’s right to be free of sexual violence and a man’s freedom to sow a few wild oats, the jurors sided with the latter” (p. 100).

Actually, it was far more likely—though difficult to say for certain without more evidence—that juries were reluctant to sentence a man to death (or to life in prison) in a case where the only evidence was the word of his accuser.

Backhouse does admit that successful prosecutions for another type of sexual misconduct, the crime of seduction, were much higher than for rape. Seduction was a special category of offence involving consensual sex where the alleged seducer was in a position of power over the complainant, such as her employer, where the girl was under age 16, or where the seducer had reputedly promised to marry the complainant. In such cases, a woman could claim that she had been pressured or duped into agreeing to sex.

Feminist historian Karen Dubinsky, in her book Improper Advances: Rape and Heterosexual Conflict in Ontario, 1880-1929 (1993) has written extensively on prosecutions, both civil and criminal, for the crime of seduction, chronicling the high conviction rate for civil cases. She notes that “Seduction cases were the most litigated cases involving women, and an astounding 90 percent of cases between 1880 and 1900 in Ontario” were resolved in favor of the plaintiff. That’s right: in 90 percent of the seduction cases brought to civil court, juries found in favor of the woman.

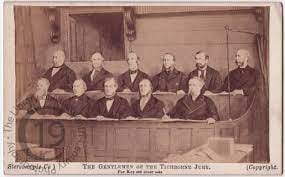

In criminal cases, the average yearly conviction rate was not nearly so high, but neither was it insignificant, especially considering the scarcity of hard evidence in most such cases: Dubinsky reports that between 1900 and 1917, the conviction rate for criminal cases of seduction was between 9 percent and 45 percent. The punishment in such cases was not as harsh as that for rape, involving prison terms of not more than two years. Perhaps juries had less trouble voting to convict when the punishment was not so drastic. Whatever the reason, it is clear that in these cases of seduction, many juries believed the woman, empathizing with her account of how she had been wronged, and willing to see a man go to prison even in cases where the woman admitted to consensual sex.

Backhouse mentions that many 19th-century criminal lawyers expressed concern over the ease with which female complainants could have a man falsely charged with either rape or seduction. She notes that “The topic of false complaints and unfounded convictions haunted the male legal community” and quotes a statement by the editors of the Upper Canada Law Journal as follows:

“But every man is fully alive to the risk he runs from the fact that, if a woman takes it into her head to charge him with an indecent assault, the chances are ten to one that he will be found guilty, no matter how strong may be the proofs of his innocence, or how weak the evidence against him. To be accused of such an offence is to be condemned. The chivalrous male juror feels that woman, as the weaker vessel, requires special protection and his notion of specially protecting her is to accept, in the face of all evidence, whatever charges she may like to bring against her oppressor.” (p. 99)

Backhouse dismisses, without evidence or argument, the lawyers’ claim as pure “fear-mongering.” Is it? If it were really the case that women were not believed when they brought charges of rape or seduction, then why would the lawyers have felt such concern over the likelihood of false complaints and wrongful convictions? If there had not been any pro-female bias amongst jurors and the public, surely accused men would not have suffered the reputation damage described by these lawyers?

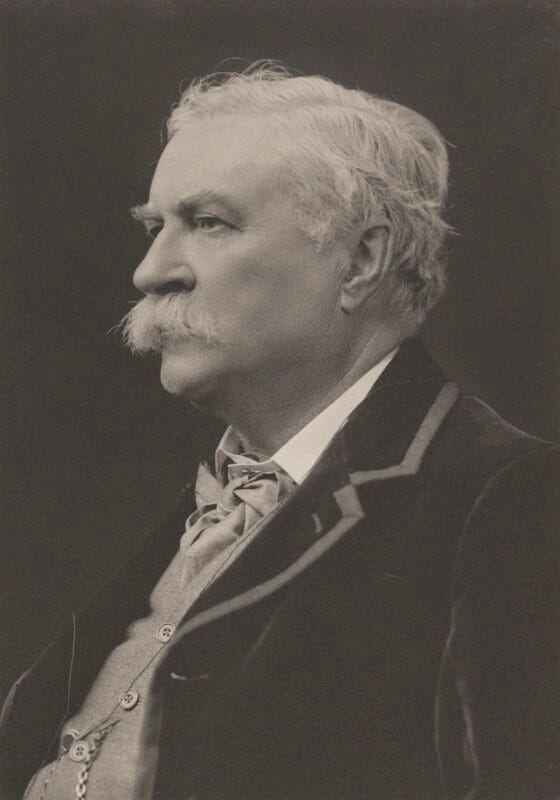

Backhouse’s example of concern amongst the Canadian Law Society, indeed, is echoed by one of the few 19th century barristers who took it upon himself to write extensively about the legal disabilities faced by accused men. In The Legal Subjection of Men (1896), Ernest Belfort Bax, a British lawyer, journalist, and historian, was appalled by the ease with which false claims of rape could be made, and by the lack of punishment faced by women in cases where the claim was shown to have been impossible. “There are no charges so easy to bring and so difficult to refute as accusations of sexual crime,” he wrote. “So well is this recognized that the most innocent man would gladly pay any sum rather than face such a charge. The only defence is the proof of a negative, always difficult and sometimes impossible, even to the most innocent” (p. 35).

Motives for women to make false charges included vengeance and extortion, and Bax contended that female accusers regularly found a sympathetic ear amongst juries, who were often reluctant, he had found, to disbelieve women’s claims of suffering. “Public opinion and the press,” he asserted, “are arrayed against [the accused]. It is not, therefore, a matter for surprise that to be accused by a woman means, practically, in the vast majority of cases, to be condemned” (p. 36).

Speaking from his decades-long experiences and observation, Bax was adamant that “every criminal lawyer knows that failure [i.e. of the complainant to win the case] occurs in only a small minority of cases” (p. 37). Citing several cases in which charges were shown to be pure fabrications, he commented further that “The total oppression inflicted by charges of sexual crime must not be measured by the cases which come into Court. It is a commonplace of the legal profession that for one such case, ten are settled out of Court. In other words, a system of blackmail of the worst type finds its direct incentive and opportunity in the present state of legal administration” (p. 37).

Bax is one of the few extant legal commentators who argued at length that, contrary to what feminists have repeatedly alleged, a pro-female bias influenced judges, juries, and public opinion in the nineteenth century Anglosphere, including in cases where women claimed rape and seduction. More detailed research is needed to reach definitive conclusions about the prevalence of convictions and the power of accusations, but it is fair to say that sexual misconduct allegations have a history far more complex than popular feminist slogans have led us to believe.

It was during the Victorian Era that the term for rape, "a fate worse than death" was coined. This suggests a crime that is taken very seriously.

Also, I would note that the Salem Witch Trials featured extremely theatrical testimony by young female witnesses. Twenty people were executed based on the testimony of these girls.