In the topsy-turvy world created by intersectional feminism, it is now impossible to say in advance what may be deemed racist if uttered by a white woman. Nearly anything, even self-denigrating expressions of racial admiration, may be judged beyond the pale.

Last week, a political candidate for the Ontario NDP (the New Democratic Party—Canada’s Gucci socialists) was forced to resign just prior to the Ontario provincial election because of comments she had previously made about black women, comments that the leader of the party, also a white woman, said were “deeply concerning.”

What exactly was concerning about the comments the candidate had made? Well—that’s where things get odd.

It turns out that Amanda Zavitz, a part-time professor of sociology and women’s studies at Western University and candidate for the Ontario riding of Elgin-Middlesex-London (pictured below), had said at a conference the previous year that she preferred black beauty to white beauty, and wanted to be black.

Speaking at a conference of the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women, Zavitz recalled another conference she had attended 10 years previously in which participants had been asked to write down a secret. Some had written about having an affair or stealing money from their spouse. But Zavitz’s secret wasn’t like those. “My secret is that I want to be a Black woman … because I think Black is much more beautiful,” she confessed. “The easy answer is that I want to be bell hooks, and bell hooks was a Black woman.”

That was enough to cause the end (temporarily, at least) of Zavitz’s political career.

Whither White Privilege?

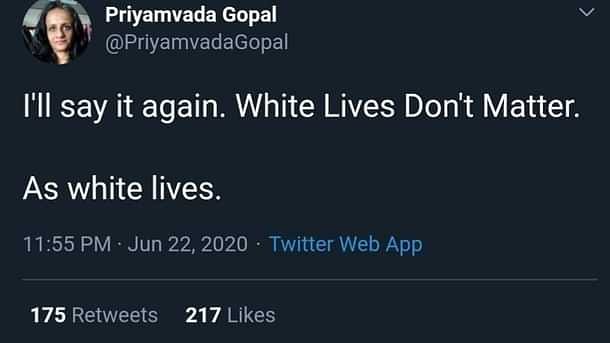

It's hard to imagine a black or brown woman being forced to surrender her candidacy because she mentioned the beauty of the white race or celebrated an icon of white feminism such as Simone De Beauvoir. Various black and brown women, in fact, have done well for themselves with objectively disparaging anti-white statements: for example, alleging that social progress will be achieved only with the deaths of older white people (thanks, Oprah!) or declaring that “White Lives Don’t Matter.”

One can almost (though not quite) feel sorry for Zavitz, whose racism seems to have consisted mainly in fantasizing about not being white—a mental pathology, perhaps, but one not necessarily directed at black women, or anyone other than herself.

Given that most of the last 40 years of feminist theorizing has consisted of exhortations to white women to admit they are racists, center the experiences of racial others, and work zealously to undo the system that confers white “privilege” (a nasty form of unearned advantage, according to sociologist and women’s studies professor Peggy McIntosh, whose work is almost certainly known to Zavitz), it is not surprising that Zavitz would secretly, or not-so-secretly, want to exchange a stigmatized identity for a more celebrated one.

Anti-white animus has been a primary theme in feminism at least since the late 1970s. Zavitz’s hero, black feminist writer bell hooks, in Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism (1982), had complained that the history of feminism showed all too clearly that white women “had not undone the sexist and racist brainwashing that had taught them to regard women unlike themselves as Others” (p. 121). Never stopping to question whether Asian or African women also saw themselves as the norm in the countries where they were the majority, hooks castigated white women for speaking as if the word woman was synonymous with their experiences, thus revealing that “women of other races are always perceived as Others, as de-humanized beings who do not fall under the heading woman” (pp. 138-39).

Always?

Having accepted this (wildly exaggerated) criticism and lived with it for who-knows-how-many years, Zavitz seems to have taken to heart the scorn and disparagement that so many black and brown feminists have been happy to mete out to white women. Although it is impossible to say anything certain without knowing the entire text of her now-disappeared speech, which I have not been able to find, it seems that Zavitz believes, with some justification, that in North American academic and political circles, black women have more cultural authority and cachet than white women. But it’s an intersectional sin to say so.

“I want to lead the fifth wave of feminism,” she told the audience, “and when you look like I do and people call you a Karen, it’s difficult to be taken seriously.” She also confessed that “The more complicated answer is that I want to know all that I know, I want to be a sociologist and a women’s studies professor. I want to be an expert in inequality with lived experiences of poverty and living in addiction and alcoholism. I want to be able to share my ideas without the barrier of looking the way I do.”

In other words, it seems that she acknowledged that she wanted to retain her relatively privileged life as a university professor (yet with lived experience, as she seems to say, of poverty, addiction, and alcoholism) but also wanted, somehow, to claim a black identity. She did not, as has been repeated on X, say that she wanted to be black “in order to gain the lived experience of poverty, addiction, and alcoholism.”

Yes, what she did say was cringe-worthy: too much information, too personal, a discomfiting mixture of guilt and envy at the intellectual level of a 15-year-old girl. It is weird and pathetic that this is what feminists are like, that Zavitz has spent time and mental energy fantasizing about how her life would be better, and her political dreams closer to fulfillment, if she were black. But is it racist? And racist against black women?

Her detractors would have it so. The Ontario PCs (Progressive Conservatives), who tracked down the video in the first place, relished the opportunity to call out Zavitz’s white tears (how quickly so-called conservatives adopt the tail-chasing values of the cultural Marxists they think they oppose). They alleged that Zavitz had “trivialized” the life experience of Black Ontarians.

But she wasn’t talking about Black Ontarians. She was talking about the subject that has preoccupied feminism for decades: the “lived experience” and attendant standpoint epistemology of racial and other marginalized groups. Zavitz merely went beyond the permissible in pointing to the reality of black female power.

The Fraud of Intersectionality

As if to reinforce Zavitz’s point, DEI advocate Nicole Kaniki (pictured above), the black director of a consulting firm that specializes in—you guessed it—diversity and inclusion, criticized Zavitz for her “lack of understanding.” Kaniki’s own statement repeatedly misrepresented Zavitz’s message in order to condemn her:

“She wants to be a Black woman to be a better advocate and ally, which really just demonstrates her lack of understanding about the Black woman experience,” said Kaniki. “It objectifies us further [sic] as if our race and gender is something that we can put on and take off and that she can put on.” [This is simply untrue: Zavitz’s whole point, crazy enough, was that she couldn’t “put on” the black female experience, which was inaccessible to her as a white woman—despite her desire for it. Notice that Kaniki seems to assume that there is only one “Black woman experience.”]

Kaniki also lambasted Zavitz for wanting to lead a fifth-wave feminist revolution: “What about making space for Black women to lead ahead of you rather than leading for them?”

Here we come to the nasty heart of the matter: the power struggle between competing groups of women, all vying for superior victim status, and the allegation that it is Zavitz’s duty to “make space” for black women to lead.

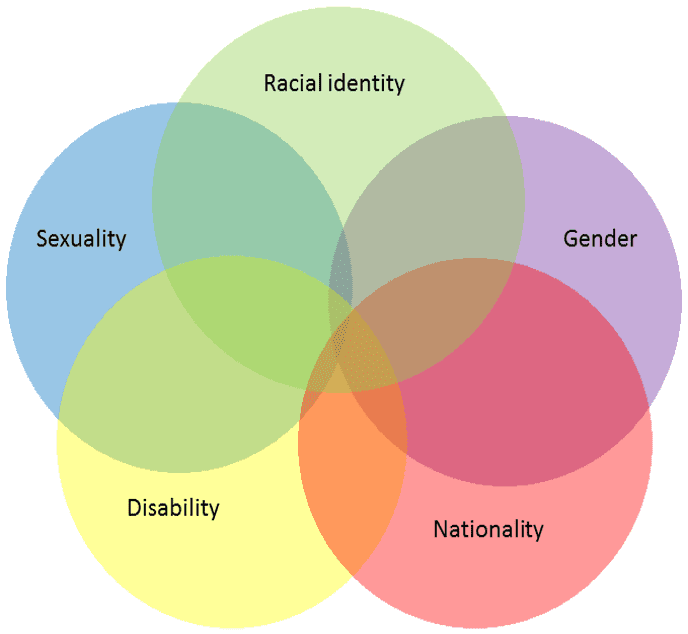

Intersectional feminism, promoted in the early 1990s by Kimberlé Crenshaw (in her essay “Beyond Racism and Misogyny”) was supposed to provide a more nuanced understanding of different women’s experiences of “intersecting” axes of oppression. In practice, it quickly spawned a near-endless contest of one-upmanship that white women were bound to lose as they competed for the “lived experience,” in Crenshaw’s words, “at the bottom of multiple hierarchies.” This race to the “bottom” (most oppressed) where one’s understanding was allegedly clearest and one’s right to speak greatest, triggered an avalanche of victimhood claims.

In sum: Zavitz lamented that, as a white woman, she was effectively barred from leading a new wave of feminism. Kaniki, a black woman, responded by telling Zavitz that, as a white woman, she should be barred from leading a new wave of feminism.

The incident, though forgettable in itself, is a vivid illustration of the whacky taboos and shibboleths that make up modern feminist orthodoxy and lay moral traps in abundance for heterosexual white women, who now not infrequently find themselves in the position of whipping boy, almost as tainted and blame-worthy as the male enemies they originally organized against.

Kaniki’s condemnations of Zavitz—for failing to understand, for “objectifying,” for taking away leadership opportunities—are, not coincidentally, the same criticisms that women in general have leveled at men. Zavitz’s sense of racial entrapment is not without foundation. She knows the paradoxical injunction under which white feminists must labor: she must not say that she understands or shares a black woman’s experience; but she must acknowledge that the black woman’s understanding is more authoritative than hers. In any dispute over meaning, the black woman will win.

The Central Park Karen

Zavitz’s naming of herself as a Karen conjures up the precise moment when white women’s loss of moral innocence moved from academia, where it had long been a factor, to mainstream popular culture.

In May of 2020, a black man named Christian Cooper (pictured above) made a phone recording of part of an unpleasant encounter he had had with the so-called Central Park Karen (whose real name was Amy Cooper, no relation, also above). In the recorded interaction, Amy Cooper tried to have Cooper arrested for threatening her and her dog. Christian conveniently omitted to record the parts of his own behavior, prior to Amy’s hysterical reaction, that were rather threatening.

The encounter quickly became an occasion for mass denunciation not of false accusations against men by women, but of white women’s alleged racism—because in reporting to police, Amy Cooper identified Christian Cooper as African American. (For anyone who still thinks the incident was as straightforward as it first appeared, Bari Weiss’s investigation is well worth considering. Christian Cooper’s recording gave the false impression that he had done nothing at all to provoke her false allegation. In fact, he had warned her, “you’re not going to like what I do.”

The assumption amidst the uproar was that this was primarily a case of racial profiling, and that if the man Amy had met in the park had been white, she either wouldn’t have made the accusation at all, or her claim to police wouldn’t have been followed up—this despite the fact that Amy’s claim was not followed up (quite the opposite: it turned Amy into a pariah and got her charged with filing a false police report). White men have frequently been accused and prosecuted on similarly hollow grounds.

Amy Cooper’s allegation was discussed as an instance of white female privilege even while that so-called privilege visibly evaporated (San Francisco even named a new law after her, the Caren Act, which allows the victims of racist allegations to sue their accusers). Following the death of George Floyd, which occurred on the same day (May 25, 2020,) there was a general outpouring of disgust at white women, with Karen used frequently as a derogatory shorthand.

At the time, some men’s advocates speculated that it might become a watershed that could contribute to a rethinking of female power to accuse men. In fact, all that occurred was heightened racial polarization, as white women were publicly shamed and tutored in the ways of righteousness in articles with titles like “What’s in a Karen,” which informed readers that Karens are “entitled” and “often racist” and “How White Women Can Be Better Black Lives Matter Allies” which told white women they “must acknowledge that they, too, have benefited from the white male patriarchy.”

Such blame and belittlement were reflected in Amanda Zavitz’s bizarre confession of envy, resentment, self-loathing, and longing.

As is evident five years after the Central Park incident, the attack on white womanhood did not represent a turning of the tide against feminism. It merely pointed to the absurd volatility of designations of virtuous victimhood. It also showed that if white women are ever toppled from their position of privilege (as yet their currency has been weakened but by no means destroyed), there will be many more self-proclaimed victims, including power-hungry black women, eager to replace them with accusatory moxie at the ready. The social pathology of feminism cannot be defeated until we recognize that social movements based on collective resentment, in which victimhood becomes a much-coveted signifier of purity and authenticity, will always find new targets for vilification.

**

I’m glad Amanda Zavitz stepped down—the last thing we need in Canada are more febrile feminist politicians with sociology PhDs—but the furor over her alleged racism was a spiteful farce.

OMG, this so reminds me of a story that Christina Hoff Sommers tells about a feminist conference she attended in NYC, in the late 80s or early 90s. All the feminists were in one room, getting along very well listening to speakers & chatting between sessions, as one does at a conference. Late in the day, the women were asked to divide into identity groups. At first the groups were large, black, white, hispanic, Jewish, etc. But then the groups began to split into smaller groups. The one example I recall was Jewish women split into subgroups with and without allergies. The upshot was, by the end of the day, there were tons of tiny groups and tons of hostility arising from the process of groups splitting and splitting and splitting.

One can't help feeling sometimes that one is in the playground of a teenage girls' school.