Sophie Lewis Celebrates Family Abolition, But It's an Antiquated and Well-Documented Failure

The desire to destroy the family is at least as old, and non-viable, as Marxist-feminism itself

Every few years, it seems, a feminist expert announces the death of the family and its resurrection in non-familial form.

The latest prophet of destruction is Sophie Lewis, whose new book’s title is an exercise in contradiction: Abolish the Family: A Manifesto for Care and Liberation. Lewis, a faculty member at the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research, argues for reimagining the family as an arrangement in which children would no longer belong to their parents (a nasty capitalist idea, apparently) but would instead be “raised by society as a whole.” This is Hillary Rodham Clinton’s It Takes a Village on steroids.

The book’s promotional blurb justifies the campaign by alleging that “Nobody is more likely to harm you than your family” (which is not technically true, as a 2019 article makes clear in citing research comparing child abuse by biological parents with that by non-family adults) and also complains that “Even in so-called happy families, the unpaid, unacknowledged work that it takes to raise children and care for each other is endless and exhausting.”

Only a Marxist-feminist could pledge with a straight face that children will be better off when they are raised by a shifting coalition of non-relatives—or that being paid (by the state, one presumes) to raise someone else’s children will be more gratifying and less tiring than looking after one’s flesh and blood.

But Lewis’s utopianism is undeterred by evidence or common sense. “To abolish the family,” she has stated reassuringly in interview, “is not to destroy relationships of care and nurturance, but on the contrary, to expand and proliferate them.” To prove this point, Lewis’s book includes a historical survey of Marxist and queer imaginings of new types of social-family.

Given that such ideas stretch far back into the nineteenth century, one is struck less by the radicalism of Lewis’s propositions than by their tired predictability and centuries-old lack of viability. Does Lewis ever stop to ponder why attempts to replace the family have never managed to sustain themselves, even on a small scale?

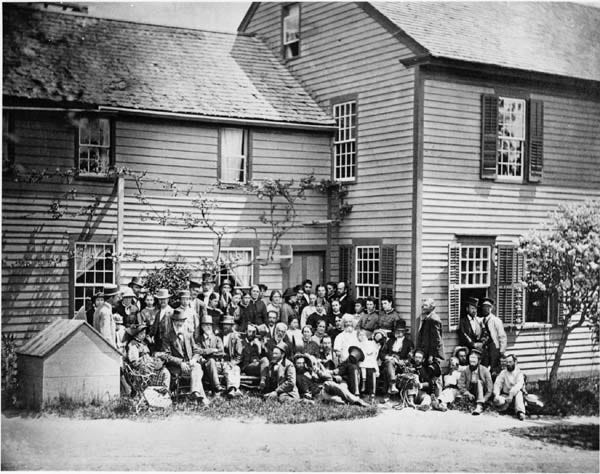

The Oneida Community in New York State, begun in 1848, was one of the most concerted efforts to practice what was then called “complex marriage” (in which monogamy and sexual jealousy were forbidden) and to raise children communally. Though it attracted some hundreds of dedicated participants, it was successful for no more than a few decades; and it foundered at least partially because younger members, raised to find collective living normal, yet wanted to form traditional families.

Does Lewis ever ponder the fact that it is mainly Marxist-feminists and queer radicals who seek a world in which caring for children could be farmed out to acquaintances? Why are such people so disgusted by the time and energy children require? Given that Lewis recently wrote an article called “Abortion Involves Killing—and That’s OK!”, I shouldn’t be surprised that the protection of infants and children isn’t high on her list of priorities.

In previous eras, feminist formulations of alternate family arrangements have often been crude enough to destroy the myth that feminism was ever about protection of the vulnerable.

When the radical eugenicist, spiritualist, and socialist Victoria Woodhull (1838-1927) spoke to thousands-strong audiences in New York City (speeches later collected in book form), she was more adept at championing sexual freedom for women than at working out how the children of “free love” unions would be cared for. In fact, the short shrift she gave to children’s needs spoke volumes about her narcissistic preoccupations.

“I am a Free Lover,” she declared in an 1871 speech, “On the Principles of Social Freedom.” “I have an inalienable, constitutional, and natural right to love whom I may, to love as long or as short a period as I can; to change that love every day if I please, and with that right neither you nor any law you can frame have any right to interfere.”

Such a formulation was undoubtedly stirring (to the loins, if not the higher faculties) but it rather starkly raised the question of who would do the parenting in this brave new world. Woodhull offered only vague promises of “ample protection for children.” Acknowledging that the “time-honored institution of marriage” was still (wrongly) revered, Woodhull vowed that something better would replace its “low and unworthy sense of mutual ownership.” “I believe in love with liberty; in protection without slavery; in the care and culture of offspring by new and better methods, and without the tragedy of self-immolation on the part of parents.”

Hers was a classic feminist formulation that admitted nothing good or honorable in traditional arrangements; imagined a glorious socialist-scientific future of “new and better methods”; and said nothing of children’s particular needs for stability and belonging. Rejecting distasteful notions of “contract” and “mutual ownership,” Woodhull was confident that better ways could simply be willed into being, and she looked forward especially to a system that would not necessitate, as she phrased it, “the tragedy of self-immolation on the part of parents.”

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815-1902), mainstream leader of the nineteenth-century American women’s movement, showed a similar willingness to smash old ways in her speech “On Marriage and Divorce” (1870), in which the fervent suffrage advocate spoke rapturously of a freedom for women that admitted no impediments—not even, it seemed, the needs of dependent children. Like Woodhull, Stanton rejected constraints on sexual emancipation in favor of a ruthless, and seemingly self-obsessed, devotion to “new amatory relationships.” What was needed above all, she proclaimed, was “freedom from all unnecessary entanglements and concessions, freedom from binding obligations involving impossibilities, freedom to repair mistakes, to express the manifoldness of our own natures, and to progress on, to advance to higher planes of development.”

Disguise it as she might with reference to Theosophical-sounding “higher planes of development,” Stanton was clear in rejecting all traditional constraints. Any “entanglement” could be abrogated, any “binding obligation” could be broken, if doing so would help to “repair mistakes” and “express the manifoldness of our own natures.” In the new era of freedom, the ever-shifting vagaries of sexual and romantic attraction would be upheld as the ultimate good of a woman’s life.

Nineteenth-century women’s libbers could be forgiven for believing in the near-infinite malleability of human nature within new social arrangements. But such have now been amply tried—in the Soviet Union, for example, and in the early days of socialist experiment in Israel—always with results that ranged from unsatisfactory to downright terrible. See, for example, Lionel Tiger and Joseph Shepher’s Women in the Kibbutz, an extensive study of Israel’s kibbutz system, in which children were taken from their parents at 4 weeks of age to be raised in Children’s Houses until adolescence, spending at most a few hours per day with their parents, who were encouraged to pursue their gender-equal work lives. Within a few generations, the Children’s Houses were abandoned—mostly at mothers’ insistence—in favor of traditional homes.

What looks like heaven to Marxist-feminist theorists feels like hell to most actual parents and their kids. And while it’s unlikely Sophie Lewis and her ilk will ever admit this, we owe it to future generations to keep on pointing it out. Indifference to the welfare of children has long been at the empty heart of Marxist-feminist advocacy.

Oh yes. the Oneida community! Wasn't that the one where all adults were expected to have sex with other adults? And the older women were the sexual mentors to the young boys and the older men were the sexual mentors to the young girls? Oh yeah, that one. lol Didn't turn out so well. Just as Janice said.

I kept wondering as I was reading this if the women involved had any children of their own. It's true that it takes a huge amount of energy to parent children but it is also true that the love we have for them will usually overwhelm the exhaustion.

Thank you Janice for another adventure into the craziness of feminist women. Well done.

This same dismantle the family agenda, unsurprisingly, was put forward by BLM, explicit on their website until it was removed after getting a little too much attention. They advocated children being raised by communities of women and ‘other caregivers’, not mentioning mothers or fathers, or men at all. In their own words, they were ‘trained’ Marxists. Now apparently they live in multi million dollar mansions.