It is being widely reported that Universal Pictures’ fictionalized documentary She Said, based on the Harvey Weinstein saga, has been a box-office bomb. According to Jeremy Fuster at The Wrap, it managed to gross only “a miserable 2.5 million from 2,022 theatres” in its first weekend, despite significant pre-release hype. Brent Lang reported that the movie’s debut “rank[ed] as one of the worst results for a major studio release in history.”

Commentators have offered predictable, if sometimes contradictory, explanations for the disappointing numbers, with most emphasizing movie-goers’ search for escapist fare. According to Fuster, films like She Said “feel like a reminder of our tough reality at a time when the general public wants a distraction from it.” But what’s a better distraction than a story about beautiful wronged heroines teaming up to vanquish a hideous villain?

Others argued that the movie was hampered by being released alongside too many other arty, serious films, including “Tar” (about sexual harassment) “The Banshees of Inisherin” (mental illness and abuse) and “Till” (murderous racism). “There’s a lot of films chasing an audience that may be a little reticent about returning to theatres,” one media analyst opined, “It may be a little too much of a good thing.”

Or perhaps too much of the predictable victim-thing. Could it be that audiences are turning off feminist and social justice-themed movies, tired of their self-righteous, angst-ridden portrayals? I’d like to think so, but it’s too soon to say. Weinstein remains the ogre we all love to hate.

**

Perhaps one day there will be a realistic movie made about Weinstein and the starlets, one that would explore the human complexities of the movie mogul as well as his compromised accusers. It would tell of aspiring actresses who had heard the rumors about Weinstein—as had everyone, apparently, in the movie industry—and yet went alone to meetings in Weinstein’s hotel room (to “discuss a script”) and came out smiling, or tearful. Whatever their feelings, these women did not go to the police. Most didn’t tell friends or family. Very few even distanced themselves from their alleged rapist.

Instead, most stayed in close contact and gushed about Harvey publicly: thanked him, made friendly jokes about him, hugged him, dined with him, appeared with him at events, clasped him for photos. It was all acting, they later claimed in self-exoneration; in reality, they were terrified, ashamed, cornered. Were they? Or were they acting later when they turned with tearful fury on the former star-maker, now elderly and in decline, and told gratuitously of his repulsive physique, his deformed penis, his rotten smell? Perhaps both displays were performances, with an equal mix of genuine feeling and self-promotion.

It seems beyond dispute that Harvey Weinstein helped these women to stardom, Oscars, and, in some cases, significant wealth, and that stardom and wealth were worth a great deal. The women were not “desperate for work,” as one commentator laughably claimed. They were eager for success, and most seem to have decided that submitting to Weinstein’s crude caresses, and staying quiet about the indignity, was a price worth paying.

The convictions in Weinstein’s New York trial, for which he was sentenced to 23 years in prison, were based on the complaints of only two women, Jessica Mann and Miriam Haleyi, both of whom had maintained close, friendly (in one case sexual) relations with Weinstein for years after the alleged assaults. As I explained in a video posted during the trial, they wrote to him lovingly (Haleyi concluded one email “Lots of love”), spoke affectionately of him to others, and sought to see him alone. Jessica Mann sent her alleged rapist hundreds of emails that never once suggested Weinstein ever harmed her. If these were assaults, they were easily preventable and enthusiastically endorsed in the following weeks, months, and years.

Even squinting hard and reciting the arsenal of excuses used to justify the complainants’ bizarre, non-victim-like behavior—and the sheer number of these justifications suggests the unsettling nature of the complainants’ acts—it takes a huge leap of faith to accept their stories of abuse and fear.

And that’s why She Said was necessary, despite its less-than-sizzling launch. The Weinstein bogeyman must be kept alive, even if few watch the movie in theaters, because Weinstein’s story is fundamental to #MeToo, giving the movement by far its strongest rationale. Even those who complain that #MeToo caught many innocent men in its vast net tend to accept that Weinstein deserved what he got.

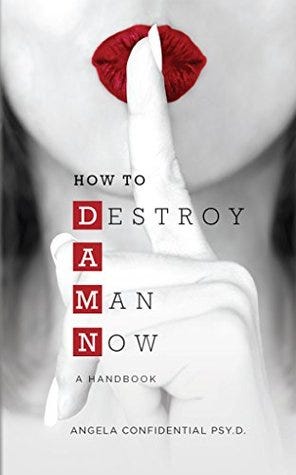

Without Weinstein, there are too few #MeToo villains. There is a long list of mobbed, shamed, fired, ostracized, and ruined men often charged with no crime, convicted of nothing, and often accused anonymously and/or without material evidence. The Brilliant DAMN Handbook—a satirical exposé of #MeToo mobbing—provides a list of 40 renowned public men brought down in a few short months in the fall of 2017. The list includes Al Franken, whose stellar Senate career was destroyed by allegations of groping. Franken, like many others, was never investigated or found guilty of anything, simply forced to resign on his accusers’ say-so.

And that is not to count the many more ordinary men who were, without any fanfare or media reporting, quietly terminated from their jobs, boycotted, expelled from college, or devastatingly slandered. Many more found themselves hauled into offices to explain themselves, given warnings, forced to undergo sensitivity training, coerced into apologies, threatened with firing. We’ll never know the number of men who killed themselves as a result of #MeToo accusations.

Weinstein is the supposed clearest case of male sexual villainy, but the atrocious conduct of his criminal trial (now to be appealed) exposes the mob mentality at the heart of #MeToo. The Weinstein trial was a spectacle of public shaming at which highly dubious legal proceedings (such as allowing Molyneux testimony from complainants about uncharged allegations), harebrained feminist theories (such as Barbara Ziv’s trauma theory), and the strength of public outrage—stoked for months before the trial began—combined to overrule the presumption of innocence. All of Weinstein’s money could not buy him impartiality; he might have been better off a penniless nobody.

Weinstein is probably not a poster boy for accused innocence—or maybe he is (out of 100+ accusations and many exposés (see, for example, here, here, and here), no material evidence has ever been produced to prove his guilt beyond a reasonable doubt). But Weinstein’s bad behavior (or actual innocence) isn’t the point. His sham trial and media scapegoating deliberately turned him into the stand-in for all the #MeToo predators needing to be “called out” and summarily dealt with. Weinstein’s conviction, along with the hand-wringing about how difficult it was for his victims to come forward, allegedly proved that other villains, not quite so reckless and unhinged as Weinstein but still undoubtedly dangerous and horrible, didn’t require a trial, didn’t deserve presumption of innocence, didn’t deserve any humane treatment or benefit of the doubt or possibility for rehabilitation—merely needed to be stopped in their tracks, once and for all, by brave accusers.

That’s why She Said, whatever its lack of success, won’t be the last we hear of Harvey Weinstein. He remains the best, and perhaps the only, chance to keep the #MeToo machine going.

Amusingly, the movie title is a tell...or a Freudian slip. The expression often used to describe rape or any sexual assault trials is "He Says, She Says". But here we just get "She Said" - unwittingly, but accurately, suggesting that "he" didn't get his fair "say" at all.

Why is Janice the only clear sighted and balanced commentator on this and related matters? Thank you, Janice, once again, for bringing sane rationality to bear on an issue usually addressed with partisan emotion and political hysteria.