Masculine heroes: can’t live with ‘em, can’t live without ‘em. That seems to be the message of many police procedurals and legal dramas.

No matter how many times these heroes save the innocent and restore order, no matter the ability they demonstrate and the risks they willingly endure, they go home to an angry, dissatisfied woman—that is, if their woman is living in the same house at all. Often, they are divorced and still in love with the woman who walked out. Frequently there is also an unhappy teen daughter (almost never a son) whose rebellion is aimed squarely at the father and whose tantrums provoke his guilty conscience. This oft-repeated story, which almost never offers a happy ending or even a workable resolution to the hero’s family woes, suggests a repressed recognition by our culture of the continual betrayal of a masculinity both maligned and necessary.

The 1995 blockbuster movie Heat offers a prime example. Running at close to 3 hours, the classic crime drama had all the material it needed for a feature-length film in the character symmetries between two men on opposite sides of the law, one an LAPD police detective (Vincent Hanna, played by Al Pacino), the other an aging bank robber looking to score one last time (Neil McCauley, played by Robert De Niro). The movie emphasizes the two men’s equivalent monomanias and chronicles the growing respect between them; ultimately, they are shown clasping hands as the thief bleeds out, having been shot by the detective in the final scene. Their intersecting public lives would have been enough for a great story.

But a number of key scenes zero in on both men’s doomed desire for love, with particular emphasis on the hero-detective’s dysfunctional domestic life, which he admits has never been good. “My life, my life is a disaster zone,” he confesses to the criminal as they confront each other across a diner table. “I’ve got a wife … we’re passing each other on the downslope of a marriage, my third.” There is also a step-daughter from his wife’s previous marriage whose sullen distress he feels helpless to alleviate, and which eventually results in her suicide attempt.

In several scenes that are quite superfluous to the main narrative, the detective’s wife berates him bitterly for his alleged failures as a husband and family man, his mental and emotional absences. On one night, he is hours late for dinner after attending a crime scene in which three Brinks guards were murdered. “Every time I try to maintain a consistent mood between us, you withdraw!” she fumes hysterically. On another occasion, the wife is outraged that he has to leave a party to attend at a murder, accusing him, upon his return, of not being emotionally “present” in their marriage.

Eventually, she becomes so desperate for his attention that she is forced, in her words, to “demean” herself with a lover, whom she brings home to their bed, in order to show her husband how he has failed her. If such behavior seems excessive and unfair, the movie doesn’t directly blame her and neither, ultimately, does the hero. While McCauley, the thief, loses his woman and pays the ultimate price for his inability to forgo vengeance, the detective who pursued him accepts that he is already, in a sense, dead, a ghost who “lives among the remains of dead people” and creates wreckage among the living. Though not prepared to change, he does not contest his wife’s characterization. He will never be able to hold a family together, he acknowledges, because he doesn’t have enough to give.

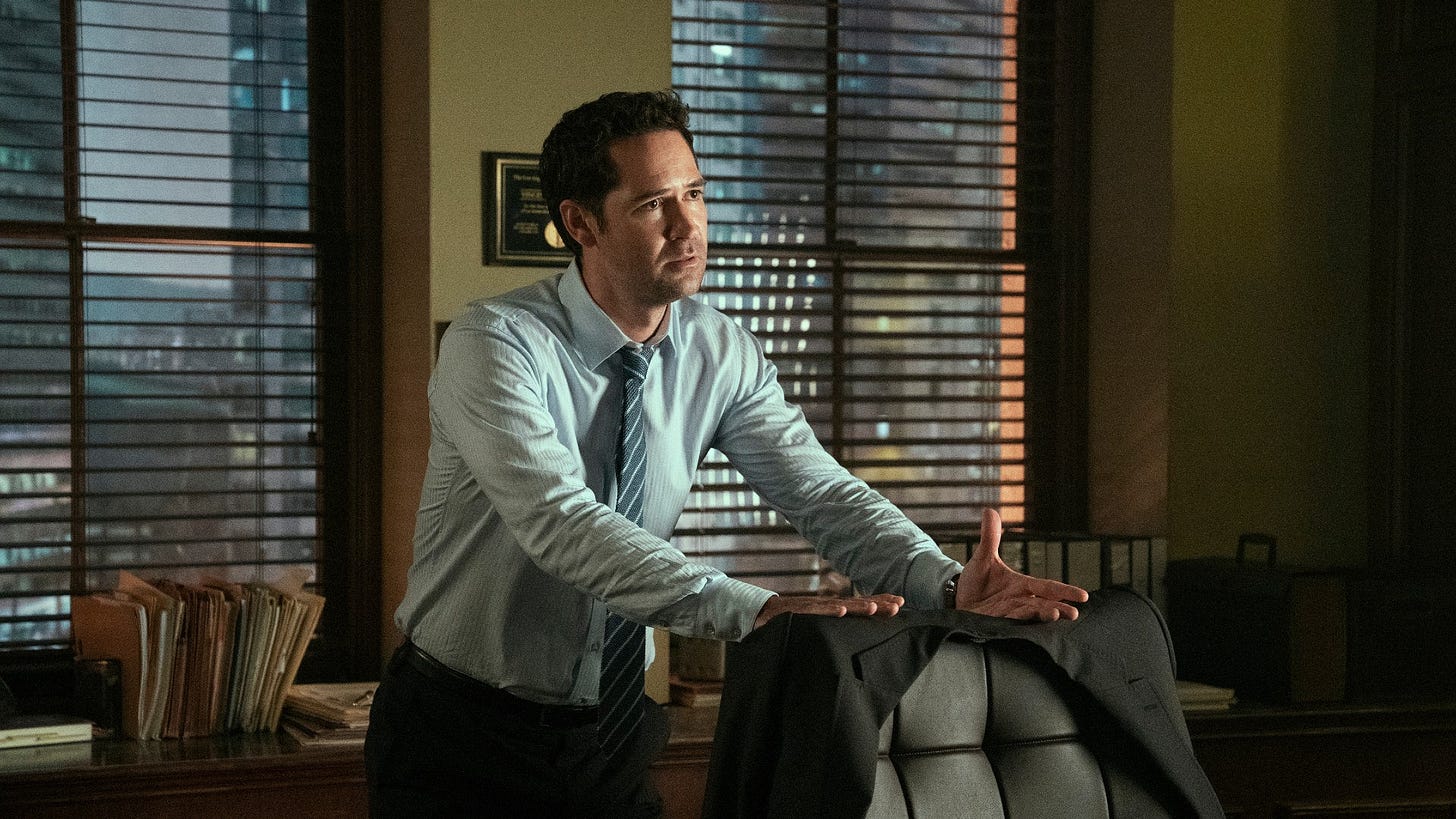

But at least he refuses to grovel, which is not the case for many other besieged protagonists. In an iconic scene near the end of Season One of the Netflix drama The Lincoln Lawyer, defense lawyer Mickey Haller puts on a contrite face under the irrational recriminations of his ex-wife, Maggie McPherson, a prosecuting attorney he still loves and is hoping to win back. When one of Mickey’s cases impacts one of his wife’s by discrediting a corrupt police officer whose testimony is central to it, Maggie interprets Micky’s work to exonerate his wrongly imprisoned client as a personal betrayal. Winning justice for his client, he is unjustly blamed by his wife.

Though she doesn’t rule out being able to forgive him one day, for now, as she tells him, their budding reconciliation is at an end. “I’ll wait,” he responds hopefully. “Please don’t,” she snaps, “Just add it to the list of reasons we don’t work.” Though she won’t apologize for her driving ambition, she expects him to do so.

Rather than fire back at her, the hero keeps on trying to make it up. “Oh Maggie,” he says placatingly as she turns abruptly and stalks from his office, “Maggie … Maggie!” His voice rises in supplication. She doesn’t stop. He picks up something breakable from his desk and hurls it against the wall, then crumples into a chair, face in his hands. The camera draws back to show his lonely, defeated figure in the darkened office.

In the next scene, he struggles to justify himself to his teen daughter, who makes it clear that she holds him responsible for the quarrel. “This thing that went down between you and Mom,” she challenges him, “Was it even worth it?” The clear implication that the mother must not be thwarted, or even made to feel thwarted, is an unspoken agreement between father and daughter. The scene is leavened, as similar ones are not, by the fact that the daughter clearly loves her father despite her disappointment in him.

But why is she disappointed at all? The question of the woman or girl’s anger arises and is never answered in any of these programs. Are we to condemn the man because he didn’t grovel harder with an emotionally volatile woman? Because he didn’t compromise his professional obligations? Because he is so dedicated to his demanding and often dangerous job that he is emotionally spent when he comes home—or because what he deals with is so brutal that he can’t talk about it? So often in these scenes of castigation, one is struck by the ludicrous inappropriateness of it all. How dare this girl berate her father? How dare this woman debase her man? And why does he put up with it?

Invariably, the contrite hero who endures his wife’s or daughter’s insults not only doesn’t deserve the attacks: he deserves love and support that he almost never receives. Struggling to right wrongs and battle evil, he has failed—if at all—only in the sense that he has not fulfilled family members’ oft-selfish personal demands. In cases where he has failed personally—one thinks of Goliath’s brilliant but self-destructive attorney Billy McBride, played by Billy Bob Thornton, who continues his legal war against dark powers even while nightly drinking himself into a stupor—it is because the intense strain of his work has sent him over the edge. But his vulnerability only seems to exacerbate the unforgiveness of female family members (McBride’s ex-wife doesn’t even try to hide her contempt).

The pattern has been replaying itself for decades, with the berating of the hero never losing its perverse punch. A 1980s British crime drama, Bergerac, starring John Nettles as recently divorced police detective Jim Bergerac, contains a scene almost identical to that of The Lincoln Lawyer. Bergerac, in love with the feisty and beautiful Susan, spends much of his time attempting to conciliate her growing discontent at his unwillingness to give up crime fighting. The classic scene of futile supplication occurs when Susan, annoyed past endurance by Bergerac’s work schedule, peels off in her car while Bergerac repeatedly shouts her name and attempts pursuit. The same dynamic characterized the 1990s British police series Dalziel and Pascoe, in which Pascoe’s marriage is frequently marred by scenes of recrimination, one when he reaches out for her in bed, with a wife who hates his work and blames him for being good at it; eventually she takes their little daughter and leaves. In the American police series Bosch, Harry Bosch’s courage and dedication count for little with the ex-wife he still loves—who has moved on and remarried—and a frequently accusatory teen daughter. And so on, in the familiar pattern.

The target audience for this classic motif is not clear. Who, if anyone, does it satisfy? Do women exult in thinking how much better they would treat their wounded hero-husbands? Or is female self-love satisfied in identifying with a defiant femininity secure in the hero’s regard? Are male viewers indifferent to the hero’s humiliation—or are they comforted to think that even such masculine paragons can be henpecked? And what do the writers think they’re doing: enacting a vicarious revenge for centuries of ostensible patriarchal oppression? Showing the necessary vulnerability of the man of steel? Offering insight into our culture’s complex expectations of men? Or simply writing what has been written before?

Having pondered these questions for a long time, I don’t have a satisfactory explanation, but I have come to the conclusion that, whether intentionally or not, these stories accentuate something central to our feminist moment, an unresolved problem in a culture that has lost its coherence. The stories express anxiety about the hero who doesn’t fight back against female assaults. They repeatedly contrast his valiancy at work—where he is still solving crimes and winning legal cases—with his helplessness at home, where he repeatedly fails to rebut calumnies by the women he loves. How can he keep on? Must he simply accept a life in which he is always being found wanting, and in which tenderness and compassion are denied him by those he loves most? Is it just me, or is this not the central question concerning men today?

Women are almost never directly criticized in these portrayals, and are almost always presented as objects of love and longing for the hero. Yet it is hard not to notice that they are not clearly worth the male effort being expended. They are certainly never expected to meet the standards of self-control, arduous dedication, and mental toughness required of the men.

Scenes in which the hero is berated by his woman or daughter are suffused with a jarring sense of unease. The hero’s faithfulness is not rewarded; his valiancy is barely recognized. He gains little in love or affirmation as a result of his efforts. Can he not demand his due?

He keeps on nonetheless, propelled by a fidelity and sense of self that require no tangible sign. Betrayed by his woman, he is on the beat or in the courtroom a few hours later, steely-eyed and undaunted. The filmmakers, and many of us watching, don’t know quite what to do with this fact, but we can’t help noticing.

**

Some of you may remember the Bechdel Test, popularized by American cartoonist Alison Bechdel, to address the representation of women in movies. In order to pass the test, the movie has to have at least two women who talk to each other about something besides a man.

Perhaps what is needed now is the Weisberg Test, created by researcher Chris Weisberg, to address the representation of the hero in movies. To pass the test, the movie has to have an unapologetic hero who is not berated but is demonstrably loved and respected by his wife and daughter(s).

I doubt many movies will pass this one.

My father was a cop, and almost certainly had PTSD as so many officers of the law do. He didn't bring that shit home with him. And he was fortunate enough to find a woman who provided the affection and emotional support he needed to stay sane. Not once did she berate him for working long shifts and having to miss important family moments due to the call of duty. That's as it should be.

You've identified an important trope in popular entertainment that I'd noticed too - otherwise strong men getting embarrassed and emasculated by bitter harridans who seem utterly insensitive to the emotional needs of the men they married, and oblivious to the duties this imposes on them. Whether this is part of a program of deliberate cultural subversion or an expression of the resentment inculcated by feminist indoctrination, the propensity of humans to emulate that which is shown to them as praiseworthy has undoubtedly destroyed many a relationship, and left many a man and many a woman isolated, broken, and miserable.

The latest Avatar movie was a welcome departure from form in this respect.

Well, let's be honest. The main thrust of these movies/shows is a man attempting to accomplish something (standard dramatic fare, see High Noon, Unforgiven, Godfather). As such there was little for a woman to do except mostly look good and be supportive. Men would take the deadly risk, women would worry . . . and if the world resolved itself, they would reunite on a buckboard out to the farm or sit down to a spaghetti dinner . . . or something else normal.

In the equality driven woke world, a fantasy, a minor character (the wife, the divorcee, etc.) has her emotive world elevated to a similar level with the big challenge. So the ex-wife's rantings, which the audience would just as soon "see" edited out, remain to add "depth" to the cop, the robber, the cowboy, the gangster.

Suddenly her "feelings" have to be dealt with as if they were as important as the main challenge of the movie. It all rings false, because the women could all just leave, or retreat off stage, and the drama would continue (and in a much better way).

So the next "solution" to the woman problem is to replace the male action hero with a female action hero. The difference is the female action hero basically kills men for 120 minutes of showtime--they are supposed to be baddies, but in the woke world all men are baddies so, ready aim fire.

Godless tried to make a town of women armed and shooting.

The English did the same with Emily Blunt.

Who knew that 1883 when a wagon went across the Great Plains that all the allies would be Comanches and Sioux and all the evil doers would be white men (bandits!!). Any other white man (the wagon train folk) would be useless and pretty much impotent. It was left to the 17 year old daughter to sleep with a cowboy and a Comanche and save the wagon train 4 times--why, of course she did.

The new formula doesn't work, though. (Game of Thrones had similar BS going on). No one will be watching this dreck in 20 years, the same way no one watches bad 70s TV anymore (the Mod Squad).