Wasn't Football Once About Stoicism?

Reaction to Damar Hamlin’s on-field collapse included public shaming and encouragement of emotional display

It was ironic that one of the first questions Buffalo Bills’ safety Damar Hamlin is said to have asked when he regained consciousness following his on-field cardiac arrest last Monday night was “Who won the game?”

It was ironic because National Football League officials had just spent days fervently denying that they had initially planned to finish the game after the 24-year-old Hamlin was rushed by ambulance to the Cincinnati University Hospital.

The decision to postpone the game was announced roughly an hour after Hamlin’s collapse. Before that announcement, ESPN had reported that teams were to be given a warm-up period before getting back into the game.

The EVP of NFL football operations expressed his hot denial at a press conference the next day. “It never crossed our mind to talk about warming up to resume play,” he stated. “That’s ridiculous. It’s insensitive. And that’s not a place that we should ever be in.” It wasn’t clear whether the “insensitive” “place” was the thought of finishing a game after tragedy, or the mere thought that the thought had occurred.

The next day, this same EVP apologized for having been “short” with his answer, but returned to his emotional theme. “It was just so insensitive to think that we were even thinking about returning to play.” A great deal, it seems, has become unacceptable in the now politically-correct world of the NFL. During the overwrought days after Hamlin’s collapse, it became clear that more than concern for the player was at issue (and whether his collapse was due to the mRNA treatments he had to take as a player, we may never know). A feminized rhetoric of sensitivity came to dominate discussion.

For anyone—coach, player, official, fan—to have wanted the game played came to represent the worst of the NFL, a (mascupathic) inhumanity that could not be too repeatedly denounced. Overnight, it seemed, it had become callous to care about football. An article in the left-wing The New Republic, no fan of football culture generally, even managed to link alleged NFL interest in resuming the game with a history in the League of suppressing sexual assault allegations against players and officials. The message was clear: bad men put football above humanity, and they deserved to be shamed.

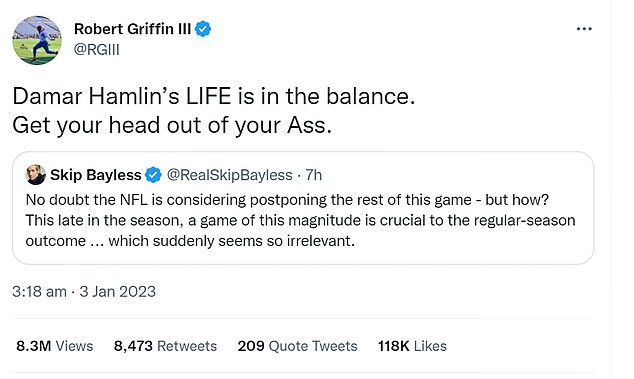

Scapegoats were easy to find. Sports commentator Skip Bayless was mobbed on Twitter for noting on the night of Hamlin’s collapse that time left in the regular NFL season was short: “No doubt the NFL is considering postponing the rest of this game—but how?” he accurately but ill-advisedly tweeted while the game’s status was still undecided. “This late in the season, a game of this magnitude is crucial to the regular-season outcome … which suddenly seems so irrelevant.”

The (butt-saving or heartfelt) addendum about “irrelevance” was not enough to mitigate howls of outrage over his suggestion that the game mattered. “I hope they fire you bro!!! For you to even THINK of the game is very sad” was typical of the sanctimonious barrage that followed: “You’re a sick individual” and “All u care about is football.” A number of football players themselves wrote self-promoting/self-pitying responses, telling Bayless that “This is the most inconsiderate thing you could have said. We are human beings not just numbers.”

Even Bayless’s on-air co-host, former NFL player Shannon Sharpe, found his colleague’s tweet so unendurable that he decided to absent himself from their show on Tuesday before returning Wednesday to denounce Bayless. It was as if the entirety of the NFL had been taken over by hysterical teen girls.

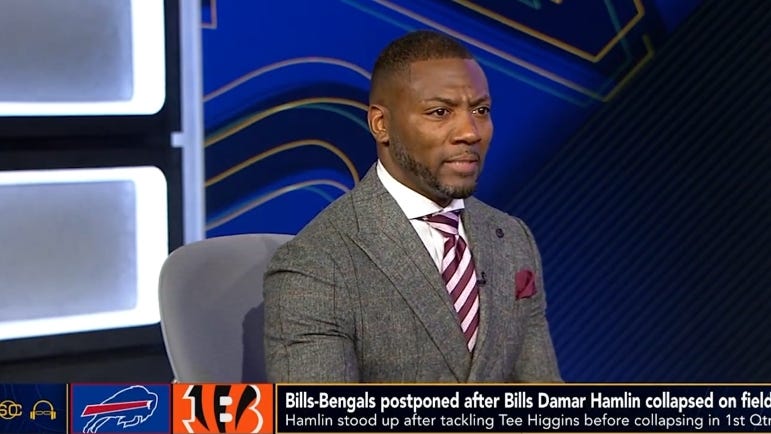

More fortunate commentators, such as Ryan Clark, a former NFL safety, earned adulation for emphasizing the “ugly side” of football: NFL exploitation and the fans’ failure, allegedly, to see players as human beings. He counselled that “the next time that we get upset at our favorite fantasy player or we’re upset that the guy on our team doesn’t make the play, and we’re saying he’s worthless, and we’re saying you get to make all this money, we should remember that these men are putting their lives on the line to live their dream.”

This (rather incoherent and trite) piece of piety was thought so important, so “empathetic,” and so long overdue that some claimed it the greatest moment of Clark’s career. “ESPN’s Ryan Clark praised for ‘empathy and humanity’ in coverage of Damar Hamlin collapse,” ran one headline. What he had said, according to sportswriter Kevin Skiver, represented a “well overdue message to those who become too invested in the stats portion of the game.” Ryan had spoken “from the heart” with a “touching” focus on “mental health.” Jeanna Kelley gushed to her Twitter followers that “Ryan Clark has me bawling right now. He’s absolutely the person we need to hear from in this moment” while Thor Nystrom nominated Clark’s commentary “the best night of Ryan Clark’s career, playing days included.” An hour or so of banal emoting, it seemed, had eclipsed Clark’s years of football dedication.

While Hamlin’s collapse prompted much talk of empathy and humanity, there was very little empathy shown for those who said the wrong thing—or merely failed to say the right thing. As cameras lingered on players weeping openly, and as we were all berated on the soullessness of thinking of stats or league realities, the strong element of coercion became almost palpable.

Football, always an emotional game, was taken over on Monday night by rank sentimentality and anti-masculine virtue-signaling, as the long process of football’s feminization—including the importation of feminist themes and female reporters—was bumped up another notch.

Sentimentality is a cultural dynamic that mandates emotional display and marks off permitted from non-permitted responses. Under the sentimental regime, specific signs and gestures, including rote expressions of grief and incapacity, become evidence of appropriate feeling. The taciturn, the stoic, the exclusively game-focused—anyone who does not or cannot express the approved emotions will be tacitly shut out.

If any player was made uncomfortable by the scene of teammates weeping at length—or found himself unable to weep—he learned to hide it.

And now it turns out that Hamlin himself, the man we were supposed to place above all other concerns, had expected the game to continue and was deeply interested in its outcome. Should Hamlin be condemned for inhumanity because, waking up in a hospital bed, one of his first thoughts was for his team’s standing? Should he be praised or pitied for putting the game above—or at least on par with—his own health?

I am, of course, being facetious. Hamlin hadn’t witnessed his own collapse. But with Hamlin now on the road to recovery, it becomes possible to say what was true all along: that thoughts of completing the game, if there were such thoughts, were never heinous, and might even have been correct. Finishing the game would have made no difference to Hamlin’s chances of recovery and would have demonstrated no lack of love or respect for the man.

Perhaps it was impossible for the players to resume. Or perhaps playing the game might have provided a much-needed source of strength and solidarity for players, many of whom communicate best not through words and sobs but through their astounding physicality.

I am a lover of the NFL for the skill, grace, and sheer genius of its plays and players. If there are ways to make the game safer, I’m all for that.

But I’m not for the feminization of the game, the ginned-up moral outrage, the posturing about victimhood, the de rigeur expressions of emotional fragility. Lavish public crying, in particular, should not become a mandated badge of honor or testament to one’s humanity. Men are men—and sport is sport—in large part because highly trained athletes have learned to control their emotions even at the worst of times in order to focus on outcomes they can affect.

Damar Hamlin was right to assume, without self-pity or resentment, that the game would go on without him, and officials or fans who wanted it to are not bad people. It seems that some commentators would like to destroy football in the name of “empathy and humanity”—weakening the players and tone-policing us all—and I hope they won’t succeed.

I was sorry for the physical breakdown suffered by Hamlin, just as I do not like to see the many injuries suffered that are directly attributable to forcible contact on the playing field. But I was appalled by the disproportionate consideration directed to this incident, given the voluntary nature of participation and the extraordinary financial and publicity compensation provided to the players.

Consider our soldiers who voluntarily risk life and limb on missions for our country, the miniscule financial compensation, and the anonymity of their sacrifices. They face the terrors of warfare in our stead, and any moment of recognition, if at all, is brief. When they struggle with the cost of their sacrifice, the Canadian government offers them government assistance to die. Homeless veterans? Just close your eyes.

Compare the concern for Hamlin with the nonexistent worry about thousands of innocent civilians, including children, assaulted or shot down and otherwise murdered in the streets of Chicago, Philadelphia, and other North American cities. Or run down by disgruntled drivers. The disproportion is sickening.

Great article. Your comment about its like the NFL being taken over by hysterical teen girls is perfect.