Will Johnny Depp's Defamation Trial Bring an End to #MeToo?

Very few with an open mind could watch the Depp trial and come away believing that Amber Heard was terrified of Depp. But we have a long history of forgiving female violence.

Some of my friends in the men’s advocacy movement are hopeful that the Johnny Depp defamation trial will sound the death knell of #MeToo—the culture of unsubstantiated, reputation-destroying accusations against men—and will raise awareness of male victims of domestic violence. Perhaps we can at last arrive at an understanding that both women and men commit violence, and that all victims are deserving of compassion.

I hope that’s true, but I don’t think it’s likely. We are as a culture continually surprised by evidence of female violence, and then immediately forgetful of it.

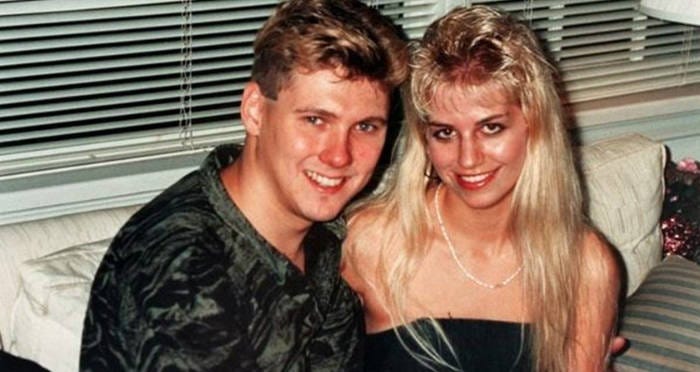

In the early 1990s, revelations about the grisly sex slayings of Kristen French and Leslie Mahaffy demonstrated that co-killer Karla Homolka, who was given a plea deal as the allegedly abused wife of monster Paul Barnardo, was at least as monstrous in her enthusiastic participation in their torture and killings.

Yet Karla Homolka was almost immediately slotted away as an extreme outlier, or perhaps merely an extreme example of Stockholm Syndrome, an abused woman who came to love her abuser and to help him harm others.

Many more such examples can be found in Patricia Pearson’s magisterial book When She Was Bad: Violent Women and the Myth of Innocence (1997), a must-read for anyone who still believes that women are, on the whole, non-violent. Pearson includes discussion of the cultural consensus that lets women get away with violence, even murder. When women abuse others, we quickly reach for mitigating explanations that allow us to maintain the cultural fiction that women are far more sinned against than sinning. Ironically, decades of feminist theorizing about the “radical idea that women are human” has not allowed us to embrace the full humanity, including the capacity for extreme violence, of women.

Very few with an open mind could watch the Johnny Depp trial and come away believing that Amber Heard was terrified of Depp, an abused spouse trying to stop his cycle of violence.

On the contrary, abundant evidence from recordings and text messages (see here, here, and here among many others) show that she was a fury, repeatedly badgering and taunting Depp, accusing and belittling him, arguing and cursing, desperate not to help him but to prevent his panicked and bewildered escape from her mockery, insults, and physical abuse. With the behavior of a typical abuser, we hear her pleading with him to return and promising to stop her abuse; also like many abusers, she seems unwilling or unable to engage in any self-reflection about the cost of her behavior, portraying herself instead as Depp’s long-suffering protector.

The prolonged exchange with Camille Vasquez, one of Depp’s lawyers, about whether a “pledge” to give money was synonymous with a “donation,” with Amber Heard repeatedly claiming that she had actually given her seven million dollar divorce settlement to charities when she had merely said that she would do so, demonstrated the extent of Heard’s stolid commitment to fantastical self-justification. Whether she actually believes her own lies or is merely unwilling to admit the truth is a matter for the psychoanalysts among us.

The fact that an abusive liar like Heard could derail the career of Depp with claims of abuse, and could actually become an ambassador for domestic violence, testifies to the dangerous credulity of our culture about female innocence. Even Heard’s own sister, who knew how unreasonable and difficult Amber could be—and has testified that she herself often needed to escape from Amber—was yet willing to watch as her sister’s ex-husband was publicly vilified as a wife-beater.

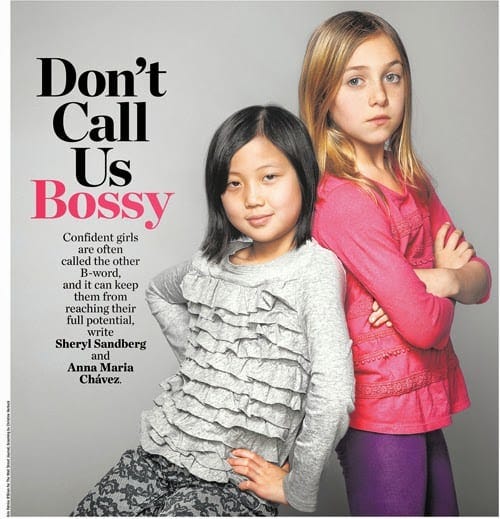

The truth is that women are allowed to be violent in our culture. We are very concerned to teach girls and young women to respect themselves, to “ban bossy,” and to be “empowered,” but we aren’t worried about teaching them to respect others, especially boys and young men. I was never once told when growing up that I should not be violent, should not hit, slap, or punch. It is assumed that girls and women are non-violent by nature. Parents, teachers, and community leaders do not instruct girls and women about the importance of controlling their anger. Instead, we minimize their violence and insist that most instances of it occur in self-defence, or do not cause harm.

As a society, we do not punish women’s violence, and we often excuse it.

Anyone interested in gender disparities in the American criminal justice system today should become familiar with Law Professor Sonja Starr’s definitive 2012 study that found “large gender gaps favoring women” in criminal sentencing—with women’s sentences on average more than 60% less severe than men’s for the same types of crimes. As Starr demonstrates, women are also “significantly likelier to avoid charges and convictions entirely, and twice as likely to avoid incarceration if convicted.” Our society’s far greater empathy for women causes them to be viewed as victims rather than perpetrators, more deserving of compassion, less responsible for bad deeds, less of a danger to society, and more likely to be rehabilitated than men.

And it turns out that this forgiving attitude has a centuries-old history.

Studies of 19th century criminal cases demonstrates that the law has, for a long time, had difficulty conceiving of and punishing female violence. Where there was any doubt as to a woman’s guilt, all-male juries were extremely reluctant to convict; and even where there was no reasonable doubt, juries were eager to find mitigating circumstances such as temporary insanity, abuse, or male coercion to justify lightened sentences or acquittal.

Professor of Social Policy Pauline Prior published a 2005 study on insanity defences used in Ireland between 1850 and 1900, and found that an extremely high number of women who killed their children—an extremely common crime—were acquitted through pleas of temporary insanity.

Women who killed adult men and women were also far less likely than men to be indicted, more often acquitted, and if found guilty, more likely than men to be convicted of a lesser crime. History Professor Kathy Callahan, in a 2013 article “Women Who Kill,” analyzed the records of felony cases at London’s Old Bailey courthouse in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, finding that English society during this period had relatively little interest in punishing women for their violence. She notes that “Society did not feel threatened by female transgressions” (Callahan, p. 1015) and confirms criminal law expert Gregory Durston’s work on female criminals in the 18th century, which found that “Females were not held to the same standards of indictment and conviction as were males” (qtd in Callahan, p. 1016).

Callahan found that in trials for violent crime, juries acquitted 61 percent of female defendants. Most indictments for murder were downgraded to manslaughter, and especially in cases where the perpetrators killed husbands or lovers, a woman’s claim that she had been previously abused by her victim often gave the jury reason to recommend clemency. Juries were also willing to believe that when men and women acted together in a violent crime, the man was the one on whom the more severe punishment should fall, based on the common belief that women were often coerced or led into criminal violence by men.

The findings of such scholars of history give the lie to the pendulum swing theory of gendered history, the idea that because women were harshly treated in the past, they are somewhat justified in demanding special privileges today. The fact is that, at least for the past two hundred years, women have exercised female privilege under law even to the extent of escaping standard punishment for murder, and have done so under the belief that they deserve such preferential treatment.

It is long past time our society considered the consequences of such leniency on women. What but diminished moral capacity—or even a completely warped morality—can result from such sustained excuse-making? If feminists and others truly believe women morally equal to men, perhaps we should at long last be willing to recognize, name, and hold women accountable for their violence.

Incisive writing Professor, and timely. Fear and consequences of censoring - dismissed from your job, socially shunned, or worse - prevent so much of the time speaking about what matters.

You are one of the shining lights for those of us men or women who have felt, or feel, trapped in the dark with this. Thank you.

Thank you for all your work to dismantle these feminist fictions that have and are hobbling western civilization. Please write a book for young women, perhaps the “real history of feminism” or “what they never told you about feminism.” It would be an instant classic.