Fear, Loathing, and Women’s Lib

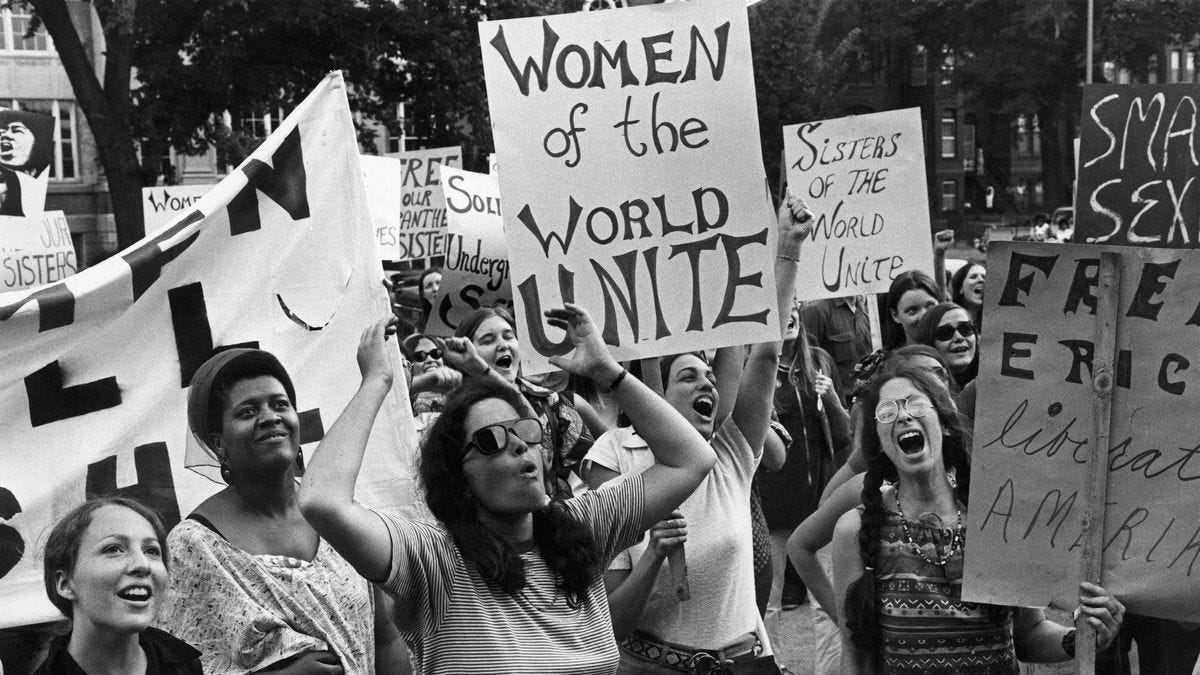

Proof in feminists’ own words that feminism causes misery and mental illness

“Hisses. Women shouting at me: slut, bisexual, she fucks men. And before I had spoken, I had been trembling, more afraid to speak than I had ever been. And, in a room of 200 sister lesbians, as angry as I have ever been. “Are you a bisexual?” some woman screamed over the pandemonium, the hisses and shouts merging into a raging noise. “I’m a Jew,” I answered; then, a pause, “and a lesbian, and a woman.” And a coward. Jew was enough. In that room, Jew was what mattered. In that room, to answer the question “Do you still fuck men?” with a No, as I did, was to betray my deepest convictions. All of my life, I have hated the proscribers, those who enforce sexual conformity. In answering, I had given in to the inquisitors, and I felt ashamed. It humiliated me to see myself then: one who resists the enforcers out there with militancy, but gives in without resistance to the enforcers among us” (Andrea Dworkin, Letters from a War Zone, p. 111)

The event described above took place in 1977 during Lesbian Pride Week in New York City. Andrea Dworkin, one of the most militant of radical feminists, a woman unafraid to condemn men to their faces, described herself as “trembling, more afraid to speak than I had ever been” as 200 of her “sister lesbians” screamed and hissed at her. Castigating her as a woman who slept with men, they demanded she place herself within approved victim categories. Dworkin’s terror of the “proscribers” and “enforcers” led her to lie in calling herself a lesbian. (As many were surprised to discover after her death, she had lived with author John Stoltenberg since 1974).

I admire this Andrea, whom I have rarely met in print, for exposing the ugly secret of feminist bullying and paranoia. I admire her for admitting that, faced with a hissing, shouting crowd of “sisters,” she felt forced to “betray [her] deepest convictions.”

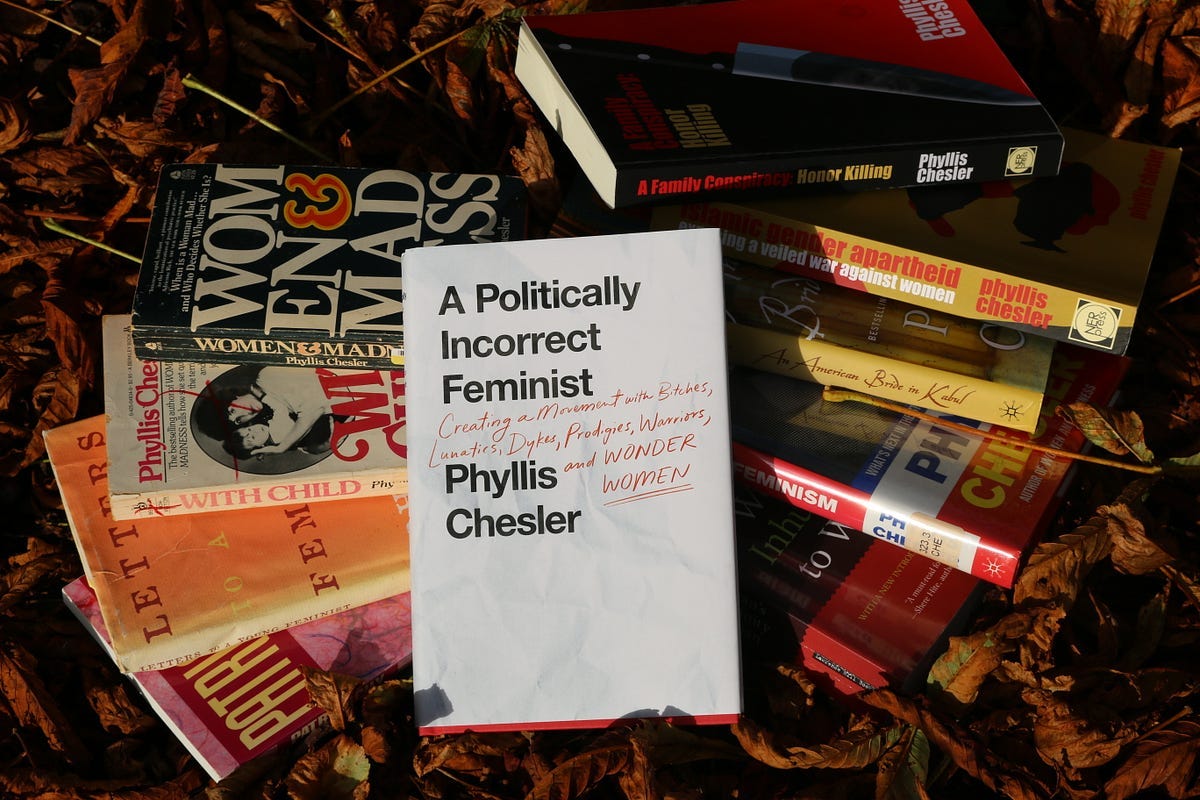

In her memoir of 1970s feminist activism, Phyllis Chesler described a very different Andrea Dworkin, a difficult woman who fought with her fellow feminists and styled herself a victim, always in the right, always under siege by those less pure. On one occasion, outraged at two feminist authors with whom she disagreed, she phoned in threats to the bookstore that was hosting an event for them. “You’re dead meat” she repeatedly told the bookstore owner, who recognized her voice (Chesler, A Politically Incorrect Feminist: Creating a Movement with Bitches, Lunatics, Dykes, Prodigies, Warriors, and Wonder Women, p. 192).

Such stories of acrimony, attack, and jockeying for power are common in feminist circles. Ask any woman who has worked for a feminist organization. She’ll acknowledge the back-biting, demands for conformity, and shunning. No longtime feminist is without war stories and battle scars.

And no feminist will draw a direct line between the extravagant nastiness of feminist women and the victim ideology of feminism itself.

In her memoir, Chesler devoted a chapter to chronicling the pain of the early years of second-wave activism: the “petty jealousies and leaderless group bullying” (p. 183), the public pillorying, the endless “ideological disputes” (p. 184). She recalls how “Mean girls envied and destroyed excellence and talent” while “Feminists who had left the Left brought with them its tactics of intimidation and interrogation” (p. 183).

Infighting at the National Organization for Women (NOW), Chesler explains, was so intense and vicious that former NOW President Karen DeCrow claimed that “Until you’ve seen a contested NOW election, you haven’t seen anything” (p. 187). One NOW member got rid of a competitor for the California state presidency “by reporting [her] to the police on a suspected murder charge” (p. 187). Chrysalis, a feminist magazine, collapsed due to in-fighting amongst writers who were “nasty, cruel, petty, insane” (p. 187). A feminist brawl at a California gay bar left one woman dead of a heart attack (p. 188).

A significant number of such women were plagued by mental illness: Chesler mentions personal interactions with Shulamith Firestone, Kate Millett, and the above-quoted Dworkin. Some had breakdowns. Some made threats against perceived enemies. Not a few committed suicide or spent time in mental institutions. Chesler admits that “many of the most charismatic and original of feminist thinkers were mentally ill” (p. 189), frequently exhibiting behavior that included “nonstop talking, yelling, paranoid accusations, drinking, stealing, [and] pathological lying” (p. 190).

When some feminists, including Chesler, tried to raise the issue of “trashing”, most feminists would not acknowledge it. Black feminists saw it as a white problem; lesbians blamed straight women, and vice versa. Most pretended that it was a sign of passionate resistance to patriarchy, thus acceptable.

Chesler herself couldn’t see it as a problem of feminism. She believed it was caused by internalized sexism, and gave what would become the classic feminist excuse: “When a human being has been diminished by heartless prejudice daily and victimized by sexual, physical, economic, and legal violence, she can become disabled, just as veterans of combat and torture victims can” (p. 188). In other words, patriarchy caused women to be cruel to each other and to themselves.

A few pages later, after giving more examples of women who persecuted their fellow activists, Chesler noted, “I can easily name twenty more feminist pioneers who were dear to me and produced extraordinary work but were disadvantaged, wounded by depression or other psychiatric afflictions. Were they depressed by how often they were on the losing end of ideological battles, by the everyday sexism that sapped their vital juices, by having to fight so hard to obtain so little because they were women? Were they at a perpetual disadvantage due to incest, rape, economic insecurity, overwork, or homophobia?” (p. 194).

Whatever the reason, Chesler asserted, it wasn’t because feminism itself, as an ideology, attracts those with mental illness or personality disorders and exacerbates the victim mentality it promotes. As researchers outlined in a 2020 article in the journal Personality and Individual Differences, the “tendency to interpersonal victimhood” is a recognized personality type that manifests in those who are obsessed with their own imagined moral purity. They demand that others recognize their victimhood, and they experience attenuated empathy for those they regard as oppressors.

It is not necessary for self-proclaimed victims to have actually experienced trauma or injustice to become convinced that their innocent suffering sets them apart. They feel entitled to behave aggressively and selfishly.

In Mary Daly’s (approving) words, “Every woman who has come to consciousness can recall an almost endless series of oppressive, violating, insulting, assaulting acts against her Self. Every woman is battered by such assaults—is, on a psychic level, a battered woman” (Gyn/Ecology: The Metaethics of Radical Feminism, p. 348). And what empathy does the battered women owe her batterers?

Even while admitting that many of the women she met in the movement were obsessed with power struggles and “victimhood primacy” (p. 184), Chesler argued that women’s aggression and mental distress were ultimately located in the patriarchal world that women were fighting against, not in the victim-obsessed ideology they had embraced.

Other feminist leaders, admitting feminists’ mental imbalance and bad behavior to other women, made similar excuses. Boston College academic Mary Daly blamed the failures of women’s separatist communities on women’s inability to “exorcise” “the specters of patriarchal presence” (p. 342). When women did not live out feminist ideals, it was because they had so far not been able to reject “the pig in the head” (p. 342).

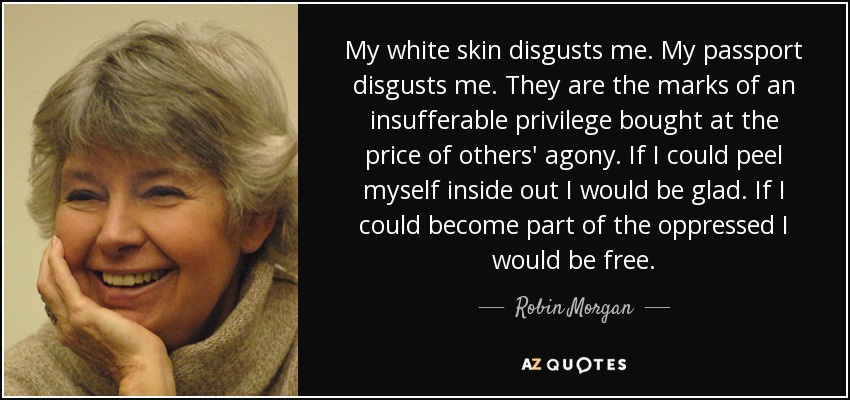

Author Robin Morgan, in the introduction to her 1978 essay collection Going Too Far: The Personal Chronicle of a Feminist, lamented that she had “watched some of the best minds of my feminist generation go mad with impatience and despair” (p. 13). She was appalled by the enthusiasm with which feminists went for one another’s throats, regretting “All that fantastic energy going to fight each other instead of our opposition! […] So much false excitement, self-righteousness, and judgmental posturing! Gossip, accusations, counter-accusations, smears—all leapt to, spread, and sometimes believed without the impediment of facts” (p. 13).

These are damning admissions, testimony to her co-activists’ untrustworthiness, lack of empathy, and lack of honor. But Morgan doesn’t follow the thought to its logical conclusion.

If many feminist thinkers were mentally ill, or at least incapable of refraining from self-righteousness, victim posturing, and fact-free accusation, what does that say about the feminism they created? About its paranoia, its warped vision of the world, its manifold accusations against men, its rancor, its conviction of innocence? If these are problems in the individual lives of significant numbers of feminist women, are they not problems for the theory of female victimhood as well?

Why should anyone take feminist women’s accusations against men seriously—in feminist so-called research, in feminist accounts of abuse by men, in claims about rape—when it is admitted that their accusations against other women have been so frequently baseless, unjust, and pathological?

Chesler maintained her ideological faithfulness even amidst frankness about feminist colleagues, insisting that “Feminism isn’t crazy, and feminist ideas aren’t crazy” (p. 189) even though individual feminists were. Why not? How can one distinguish between a crazed feminist individual and her crazy-sounding arguments?

Robin Morgan, describing the cliques and endless civil wars within and across feminist groups, could only fall back on the need for more feminism to cure these ills. “I’ve come to think,” she declared, “that we need a feminist code of ethics, that we need to create a new women’s morality, an antidote of honor against this contagion by male supremacist values” (p. 13).

Women’s cruelty to other women, then, was an expression of “male supremacist values” rather than a reflection on the women themselves, whom Morgan was sure could offer a superior “feminist code of ethics” to save their shattered unity. Disharmony, back-biting, and even deliberate assault did not disprove feminist claims about superior female morality; they merely made it all the more urgent that feminism be affirmed and implemented.

This became a lynchpin of feminist thought. When men did wrong, it was because they were men; when women did wrong, it was because they were victims of men.

Only Andrea Dworkin, in the article cited above, made the opposite point, rejecting the attractiveness of the female exemption. Women’s belief in their moral superiority was an ethical flaw, she asserted, and “Nothing offers more proof—sad, irrefutable proof—that we are more like men than either they or we care to believe” (p. 115).

Dworkin had been outraged and ashamed on the night she experienced her lesbian sisters’ bullying and their delight in self-righteous hatred. If she had remained true to these insights, she might not have pursued her subsequent feminist career.

I believe John Stoltenberg was gay and Dworkin bisexual (she herself being for the most part celibate) and that their marriage was more in the way of friendship -- though I could be wrong. Her hatred of men stemmed from at one time being raped and also having been a prostitute. I read her books years ago -- all of them actually.

She is a good writer but her misandry is out of control. "Our Blood" is her most militant tome. Dworkin was among those who gave us the false idea of "rape culture" -- which is now widely promoted in the education system. She was a revolutionary who wanted the destruction of Western civilization -- and to a remarkable degree, her wish is being fulfilled.

Dworkin is right that the enforcers within the feminist movement are frightening. And that is true of all Leftists because Leftism relies on a mob mentality and the dynamic of scapegoating. This is not incidental; it's at the heart of Leftism, based on a collective sense of identity and groupthink. Thought crimes, and ideological heresy, are the worst sin of the Leftists.

Personal morality and egregious breaches of it don't matter; what matters most to Leftists is adherence to ideology, and affirming one's identity as part of the collective. It's cult-like. The fear comes from having that identity stripped from you, of becoming worthless not only in the eyes of your comrades but in your own eyes. If your entire identity is tied to this belief system, it can be used to control you. And that is exactly what happens. This fear is a way for the authoritarians in the movement to wield power over others.

Those scapegoated by the collective will typically contemplate suicide. They experience existential dread. Conversely, the sense of belonging in the collective brings with it a feeling akin to religious ecstasy, of euphoria at having meaning and purpose in life (as prescribed by the goals of the movement). All Leftists experience the lure of this sense of self and the fear of losing it and becoming reviled.

Apostates and heretics from the movement are regarded as evil and worthy of the worst punishment, of public shaming, doxxing, and violence. I have witnessed and experienced the wrath of the feminist collective many times and it's like watching a lynch mob hang a man. But it's less obvious to conservatives that this same dynamic is what keeps the Leftists themselves in check and easy to control.

A totalitarian society is simply one in which the entire society experiences this social dynamic. Feminism has moved from a marginal movement of a few thousand angry women more than a century ago to a movement that has overtaken the entire Western world. It has done more damage to women and children than any other force in history, in my view, relegating them to profoundly sad and lonely lives. It has been bad not only for men but also for women because it was never about womens' rights as much as it was about hatred of men.

Feminism also teaches young people to blindly obey authority, even when it's wrong, and it presents a simplistic and erroneous view of history and the human condition, brainwashing girls and women into the false belief that they are victims. It is taught from an early age in schools and now in the movies. It does all this, like other forms of cultural Marxism, through fear of censure, as described in this article, and through a relentless stream of propaganda.

Is it narcissism or just stupidity that makes those who populate certain movements claim that those who disagree simply don't know their own interests? If a woman disagrees with feminism, she's "internalized the patriarchy." If a black person disagrees with critical race theory, then they've "internalized whiteness." If a blue-collar worker doesn't buy into communism, they just don't understand their true interests, i.e., those of the working class (all of whom have identical interests as workers). And the people who do know the true interests of women, blacks or blue-collar workers are never the individuals themselves, but feminists, extremist blacks and communists. The rest of us of course understand that those ideologies have no concept of individual differences or that people aren't just categories, because doing so would necessitate the dismantling of the ideology as the all-purpose analyzer of all things human. Which brings me back to my original question.