How To Do Things with Numbers, Feminist-Style

A new domestic violence campaign demonizes men with false numbers and shameful misrepresentations

“Linden called on men and boys to educate themselves on violence and to call out one another for perpetrating or dismissing abusive behavior of any kind.”

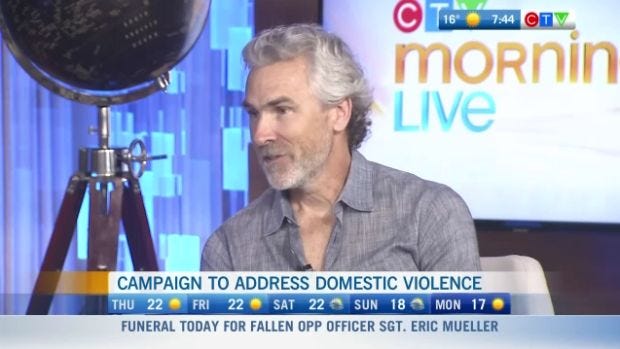

It’s not hard to understand why National Hockey League personality Trevor Linden, former captain of the Vancouver Canucks, has lent his star power to a YWCA campaign about women’s injuries from domestic violence. Hockey players have long been targets of feminist accusation for their association with a sport that allegedly promotes misogyny, racism, and violence against women. Even a beloved icon of the sport must continually strive to prove how much he despises his fellow men.

In this case, the campaign of vilification targets the purported frequency with which female victims of intimate partner violence (IPV) experience traumatic brain injury, and demands “increased support for diagnosis and treatment.” To do so, the campaign asserts some of the most dramatic numbers I’ve ever seen.

No stranger to concussions, Linden is said in a CBC report to have been “stunned” to learn that female victims are injured at a much higher rate than professional hockey players. “For every concussion incurred by an NHL player,” the report states, “approximately 7,000 women and girls in Canada are concussed because of intimate partner and domestic violence, according to a new estimate from YWCA Metro Vancouver and researchers at the University of British Columbia.”

Linden’s shock is understandable. We’ve all seen the hits meted out to professional hockey players. The thought of thousands upon thousands of Canadian women every year being treated in like manner—and suffering the consequences in traumatic brain injury (TBI)—is disturbing even to those of us who have learned to be skeptical of feminist research and inflammatory reports by Canada’s state-funded news agency.

The key paragraph in the story that justifies the staggering numbers tells us that

“Approximately four in 10 women and girls in Canada will face violence from a current or former partner, according to a 2021 report by Statistics Canada, or about 290,000 every year. As many as 92 per cent of them will suffer a traumatic brain injury due to blows to their head or strangulation.”

That sounds as if more than 3 in 10 women and girls in Canada (92% of 4 in 10) will at some point in their lives suffer brain injury from battering.

The statement might just qualify as the most outstanding exaggeration of violence against women ever made by a feminist organization. The good news for women and girls in Canada—and the bad news for the ever-declining credibility of feminist advocates and reporters—is that the numbers being promoted are flat-out false. They’re false even if we take note of the operative word “approximately” in the above statement. They’re false even if we accept the extraordinarily elastic definition of violence employed by the feminists who work for Statistics Canada. And they’re false even if we accept that a small study of black female victims of extreme violence can be generalized to all girls and women in Canada.

The numbers are false, ultimately, because the literature review from which the 92% number was extracted does not actually claim that 92 per cent of all IPV victims experience brain injury. A fundamental misreading and misrepresentation of data is at the heart of the campaign’s extraordinary claim.

Let’s trace, as much as possible, how the numbers have been manipulated and fudged. At the center of the hoopla is a report from Statistics Canada (“Intimate partner violence in Canada, 2018: An overview”) based on a large survey conducted by online questionnaire and telephone interview. This government-funded survey sought to measure the experience and frequency of intimate-partner violence as reported by victims—both men and women—over the previous year and over the lifetime of each victim. The sample size was large (43,296) but the response rate was low, at 43.1% overall in the Canadian provinces. (It is worth noting that response rates lower than 60% are considered by some researchers to produce unreliable and invalid results.)

The report on the survey data states early on (top of p. 5) that “More than four in ten women and one-third of men have experienced some form of IPV in their lifetime.” This is clearly the basis for the campaign statement about “four in 10 women and girls” facing violence. One need not ask why the authors of the violence campaign chose to omit the “one-third of men” who have also reported IPV. The campaign is clearly meant to focus on men as sole perpetrators, not to demonstrate parallels between male and female experiences of abuse, and certainly not to suggest that women are also perpetrators. Naturally, the Statistics Canada report accepts that every claimed act of violence was an actual act of violence, never considering that respondents might be mistaken, confused, or less than scrupulously honest.

The report has a detailed section (p. 4) on what the survey counts as violence. It turns out that violence doesn’t necessarily have to be, well, violent. It can be “psychological violence,” for example. That category includes “jealousy, name-calling, […] manipulation, confinement, or property damage.” Frankly, I am surprised that the number of respondents claiming to experience this type of “violence” was as (relatively) low as it was. Most of us have at one point or another felt chafed by a partner’s “jealousy” or, depending on our sensitivities, “name-calling” at least once. Regardless of whether such should be counted as violence, it’s clearly impossible to see how any of these types of “abuse,” unpleasant as they may be, could result in a brain injury.

Physical violence, as it turns out, is also not necessarily violent: it could involve “the threat of physical assault” or could involve “items being thrown at [not necessarily hitting] the victim.” Depending on what the item was, the level of violence involved here may be low to non-existent. Some of us remember that a Florida man was arrested in 2019 for throwing a cookie at his girlfriend.

Sexual violence is also counted as violence in the survey, including “threats of sexual assault” or “being made to perform sex acts that the victim did not want to perform, and forcing or attempting to force the victim to have sex.” Again, these may well be unpleasant and abusive, but it is hard to see a direct relationship between concussion and such forms of abuse or attempted abuse.

The Statistics Canada report does enumerate the different types of reported violence (see Table IA, pp. 15-16), but even the detailed breakdowns are not very helpful. For example, there is a single category made up of “shook, pushed, or threw you.” To be “thrown” seems a distinctly different level of violence than, for example, being “pushed.” A man whose girlfriend was yelling at him and blocking his way out of a room might well “push” her as he struggled to evade her verbal harassment, and most people would not see this as violent abuse; but it is counted as such in the survey. Similarly, there is “Thrown anything at you that could have hurt you,” which is, again, a vague category open to interpretation. Most importantly in relation to the campaign claim about brain injury “due to blows to [the] head or strangulation,” there is a category for “choking” but there is no category for “blows to the head.” The Statistics Canada survey is thus not a good tool for substantiating claims of widespread concussion from IPV.

Perhaps most significantly, the survey did not ask about severity of violence, and we have no way of knowing from the survey what percentage of respondents sustained injuries as a result of the reported violence or needed medical treatment for their injuries. In sum, the survey provides a snapshot of respondents’ claims of violence, but no independent verification for the severity or even, as already mentioned, the veracity of the claims. Such omissions and lack of verification almost certainly lead (and are designed to lead, one must conclude) to an inflation of the number of claimed victims. As the report’s author admits, “The analysis presented in this article takes an inclusive approach to the broad range of behaviors that comprise IPV. For the purposes of this analysis, those with at least one response of ‘yes’ to any item on the survey measuring IPV are included as having experienced intimate partner violence, regardless of the type or the frequency.” A woman who recalls experiencing “name-calling” on one occasion 20 years prior will be lumped in with all the others as a potentially concussed victim of IPV.

I was unable to find the afore-mentioned number 290,000 in the StatsCan report, which focuses almost exclusively on percentages. The key data table (Table 1A, pp. 15-16) provides a total percentage of 44.1% lifetime IPV occurrences for women, as well as the (never acknowledged) 36.1% lifetime IPV for men. It is not clear how these totals were arrived at because the totals cannot be obtained from adding together the figures provided in the itemized lines. Regardless, the numbers almost certainly form the basis for the claim about “More than four in 10 women and girls” victimized in their lifetimes. It is impossible to accept, however, that a high percentage (and certainly not 92%) of these self-reported “victims" suffered any kind of brain injury.

The concussion campaign report includes another source of data, this time a small study of black American women, to bolster its extravagant numbers. Entitled “The Effect of Intimate Partner Violence and Probable Traumatic Brain Injury on Mental Health Outcomes for Black Women,” this study mentions the 92% figure, though it provides that figure in the study’s background discussion, not as an actual finding (more on the actual findings shortly). In an introductory section, “Traumatic Brain Injury as a Result of Intimate Partner Violence,” we are told that “Between 40% and 92% of IPV victims have sustained head injuries and nearly half have been strangled.” The reference takes us to yet another paper, where we read that “A review of literature conducted on TBI from IPV found prevalence of 60% to 92% of abused women obtaining a TBI directly correlated with IPV.”

Here, then—leaving aside the discrepancies in numbers—is how the magic was worked. We have a study of women with traumatic brain injury. The study found that up to 92% of the women with TBI received the injury from partner violence. But that does not lead to the conclusion that of all women who report partner violence (much of it not particularly violent), 92% of them will suffer traumatic brain injury.

Even in cases of extreme violence, studies show, rates of traumatic brain injury may be much lower. The study of black women’s mental health examined 95 black women who experienced severe physical IPV; their injuries included “loss of consciousness from head injuries and/or strangulation.” The women also had a history of abuse that included “forced sex and childhood maltreatment.” Clearly, their experiences of repeated severe violence and loss of consciousness cannot reasonably be mapped onto that of the much more heterogeneous Statistics Canada cohort, many of whom did not experience actual violence. Even in the case of the severe violence, the study found that “about one-third [not 92%]” of the abused black women “had probable TBI.”

We are a long way from tens of thousands of women suffering concussions every year—something that can only be considered a case of myth, not math.

Trevor Linden has almost certainly not looked into either of these background data sources. He was simply shocked to be told that “survivors of domestic violence are concussed” at such horrific rates—and why would he question academic feminist researchers and reputable organizations like the YWCA? One might have hoped that a reasonable person looking at the reported numbers, merely thinking about them for one minute, would have been forced to conclude that something was seriously amiss with the story. But very few people question such numbers because to do so is to find oneself accused of complicity in women’s pain.

Thus, I don’t judge Linden too harshly, despite his support for a shaming lie that will more than likely contribute to men being falsely accused and harshly punished. The desire on individual men’s part to escape condemnation is natural, and the temptation to publicly defend women against alleged male violence must be hard to resist.

As I hope to have shown, however, it is long past time to withdraw our reflexive trust in feminist organizations hyping up extravagant proof that women are even worse off than previously thought.

Clearly the message to be taken from this is that more Canadian women need to get their skates on and take up competitive hockey, where they would be immeasurably safer than they would in the conjugal kitchen, where all manner of baked goods risk putting an end to their cognitive functions.

Good article. Data manipulation is everywhere, and it is getting worse. There is very little (read: none) information today that is published in the MSM that one can take at face value. My professional sector is energy, and the MSM misinformation about the subject is literally out of control.