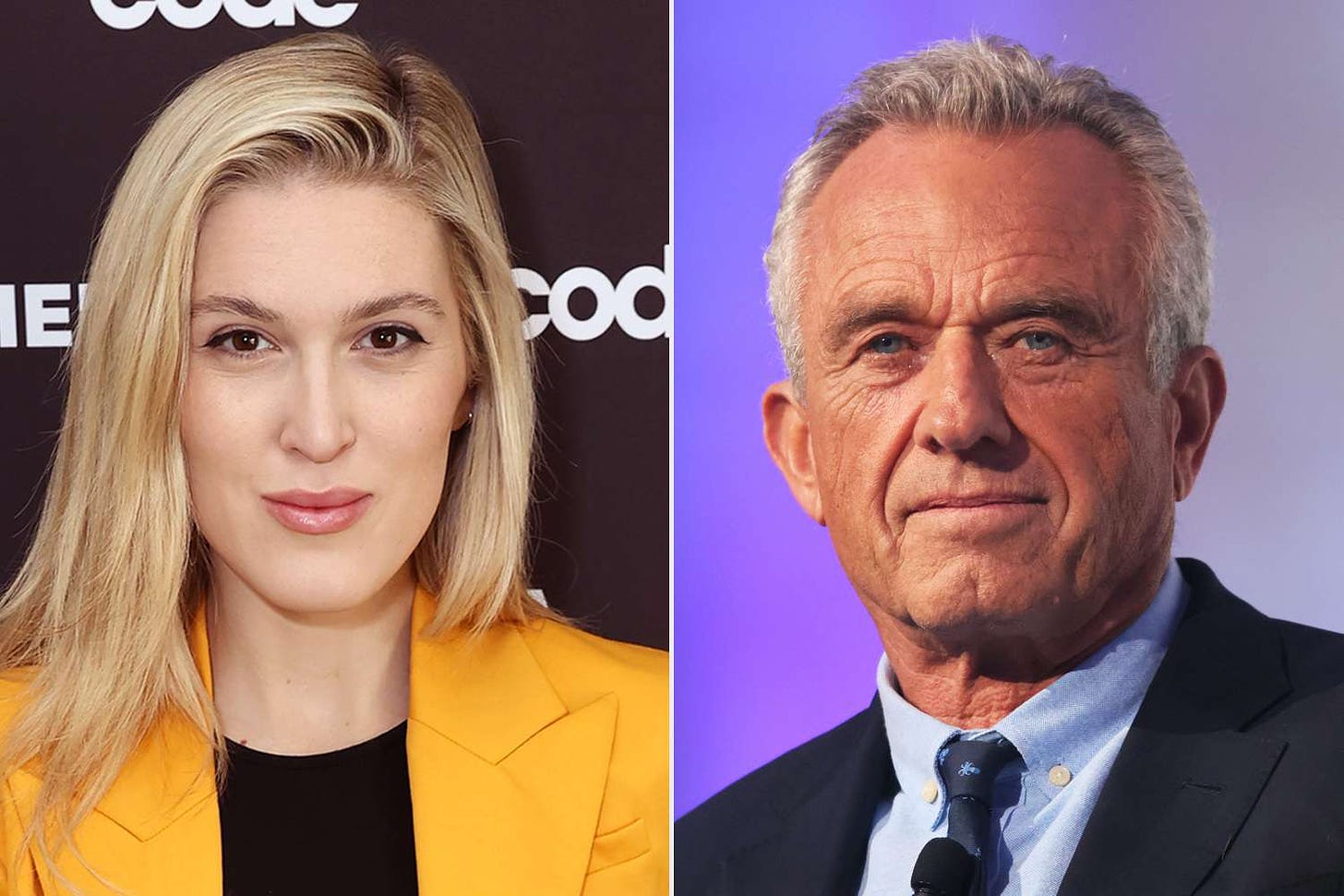

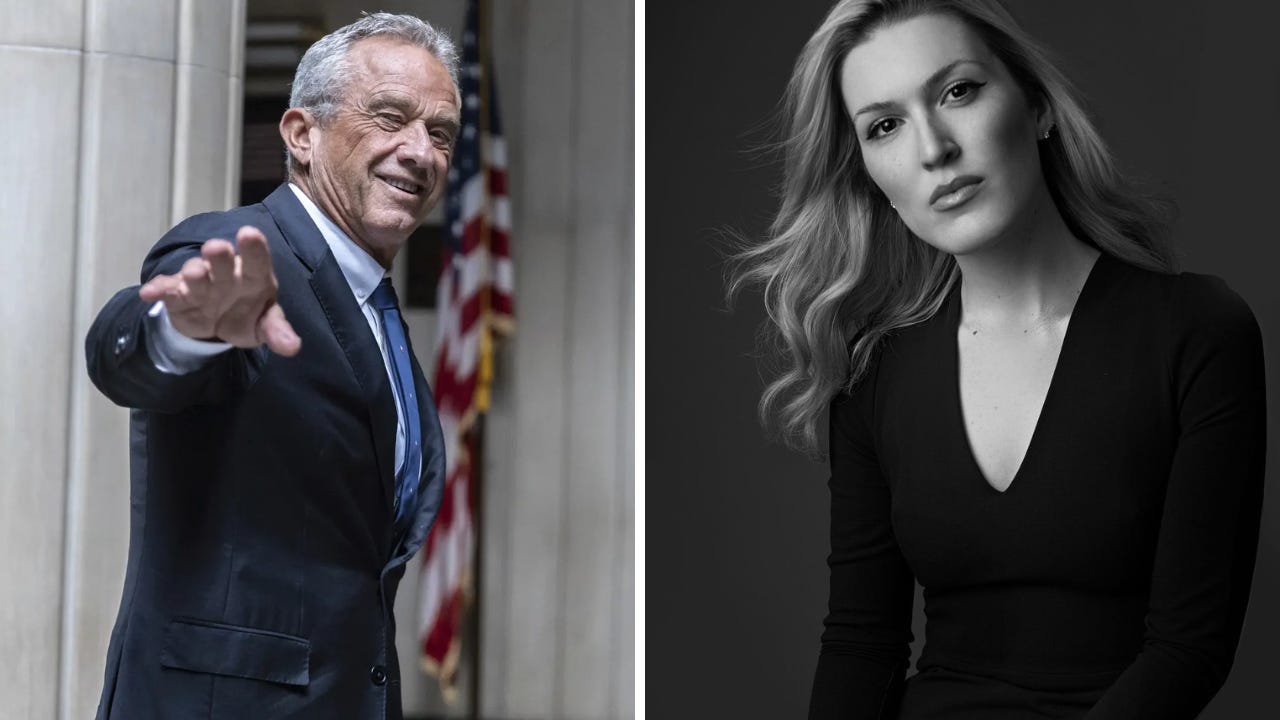

It’s Impossible to Cry Woman-as-Victim in the Case of Olivia Nuzzi, the Journalist who Sexted RFK Jr.

But that won’t stop feminists—and Nuzzi herself—from trying

Even an anti-feminist satirist couldn’t have constructed a better allegory of contemporary gender politics, including stark double standards, a feminist journalist dead-set against “slut shaming,” and a pouting femme fatale posing as a victim.

Feminism has achieved one certain thing: it has made it difficult to have a non-hysterical discussion of women’s sexual misbehavior.

Cue the alleged “sexting scandal” between buxom New York magazine writer Olivia Nuzzi and former presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy Jr., two beautiful people whose indecent attraction went public last month.

In the absence of further evidence, it seems that Nuzzi, who was at the time engaged to fellow journalist Ryan Lizza, pursued and wooed RFK Jr. from about November of last year until August, when news of the affair broke. In a recent Substack essay, Jessica Reed Krauss, friendly with both Kennedy and Nuzzi, described how Nuzzi initially flirted with Kennedy during an interview last October and then began bombarding him with suggestive phone calls and texts, including pornographic photographs (to my knowledge, never published).

It isn’t clear whether Kennedy requested the photos Nuzzi sent him or was initially happy to receive them (Krauss thinks he was). They never met in person again. Ultimately, Kennedy made it clear to Nuzzi that he did not wish to communicate with her, blocking her phone number for periods of time. Perhaps he feared for his marriage (now reported to be on the rocks). For her part, Nuzzi made up excuses to talk with him, at one point claiming that she had urgent information about an upcoming political hit piece; as soon as he unblocked her number, she began once again sending him sexual pictures. Krauss thinks that Nuzzi may have been genuinely infatuated by Kennedy, or was stringing him along in order to discredit him.

It need hardly be said that if RFK Jr. had sent nude photos of himself to Nuzzi, persisting even when she blocked him, and finding dishonest ways to get around the block, most people would know what to call his behavior and who to blame. He would be perceived as a sexual harasser, perhaps a stalker, and would be considered guilty of serious misconduct and abuse of power.

When the shoe is on the other foot, of course, most commentators are not sure what to say. We’ve all had it drummed into our heads that when the subject is sex, the woman is always innocent.

And as in all cases of female misconduct—up to and including the murder of children, as I have shown here—our culture is deeply unwilling to see (especially attractive young) women as either culpable or dangerous.

Nuzzi has been placed on leave while the New York magazine investigates her actions, and the editor-in-chief’s comments have focused exclusively on a potential “conflict of interest.” As reported in The New York Times, Nuzzi may have been “personally” involved “with a former subject relevant to the 2024 campaign while she was reporting on the campaign.” The admission is low-key. Nuzzi’s own words are quoted without evident skepticism: “Some communication between myself and a former reporting subject turned personal,” she has admitted (just like the tide turned, one supposes—nothing to do with her actions). Nuzzi is described by the Times as having “a reputation for sharply written and deeply reported political features.” NPR turned away even more resolutely from salaciousness, noting the editor-in-chief’s concern that Nuzzi has “potentially damaged our readers’ trust” and stressing that a preliminary review of Nuzzi’s published work since the time of her involvement with Kennedy found “no inaccuracies nor evidence of bias.”

Such reports do not mention Kennedy’s claim that the alleged “personal” connection was largely one-sided, that Nuzzi pursued him for months. An unnamed source told the New York Post that “She went after him aggressively […] It was a little scary.” Another report notes that Kennedy has hired a lawyer to consider civil or even criminal charges against Nuzzi, who allegedly “‘bombarded him with increasingly pornographic photos and videos’” while “tricking him into unblocking her numbers.”

Nuzzi’s “deeply reported political features” have more than once involved erotic interaction with interview subjects, in which Nuzzi’s evident attraction to wealthy, powerful men was a major part of the story (take a look at her pouty tete-a-tete with billionaire Mark Cuban, which highlights her teasing infatuation). Placing her sexy self at the center of stories has long been one of Nuzzi’s favored techniques. Her first publication, a mocking account for the New York Daily News about interning for soon-to-be-disgraced Anthony Weiner during his mayoral campaign, led Weiner’s communications director to fume that Nuzzi was a manipulative “bitch” who “was clearly there because she wanted to be seen.” Such details paint a picture of Nuzzi as a fame-seeker attracted to powerful men, a woman who has never been averse to using her sexuality for personal advancement and pleasure.

Not all young female journalists act like Nuzzi, of course, but it would be ludicrous to pretend that she is a one-off. As John Leake argues in his “On Predatory Women,” she takes her place in the tradition of femme fatales, who were once recognized as dangerous to men and to the social order. Fascinating yet heartless, they are notable for their blithe destruction. Now, however, most people are afraid to criticize them.

Of all the commentary on this story, the one I found most revealing was feminist Moira Donegan’s “The real victims of Olivia Nuzzi’s affair with RFK Jr are other female journalists” in The Guardian. As the title makes clear, Donegan was determined that there must be a female victim (or victims) in the case, so she chose women like herself, allegedly now “embarrassed by unfair comparisons.” Donegan would prefer the victim to be Nuzzi also—and then by extension every vulnerable, sexually exploited young woman in the world—but even an ideologue like Donegan couldn’t turn the 31-year-old Nuzzi into an appropriately terrorized damsel.

Besides, Donegan dislikes Kennedy, whom she calls “the anti-vax crusader, animal corpse desecrator, former presidential candidate and brain worm host,” and detects a failure of feminist rectitude in Nuzzi, who has “routinely cozied up to powerful Republican players” and was engaged to a man “fired from the New Yorker in 2017 for alleged sexual misconduct.”

But how to criticize the woman now, given that her offense was sexual? Donegan’s caution is salutary. Charging that much of the reporting about Nuzzi has delighted in “the sexual humiliation of a woman” (I haven’t seen it), she asked how “we criticize the actions of patriarchal women without falling into the trap of perpetuating misogyny against them.” It is misogynistic to “slut shame” a woman, Donegan asserts, for “flattering the egos of men who could get her jobs or serve as sources,” trading “sexual attention for professional opportunity.”

Here is feminism to a T: not about equality or justice, and certainly not about ending sexual harassment in the workplace, but about forbidding criticisms or restraints on female sexual power. Nuzzi can be criticized, Donegan makes clear, only if she can be seen to hurt other women, in this case by applying a (sexual) leverage that not all women have or want to employ; and thus allegedly encouraging men to think that other women will do so. The behavior in and of itself (the lack of womanly honor, the lying, the refusal to take responsibility) can never be the issue.

It would have been simple enough (and a good move likely to have killed the story) for Nuzzi to apologize publicly, including to her fiancé, admitting to an illicit infatuation that she couldn’t or didn’t stop. But when was the last time we saw a woman make a full public apology of sexual wrong-doing?

Now it turns out that Nuzzi—not such a “patriarchal” woman after all—is going on offence. She has accused her former fiancé, Ryan Lizza, of blackmailing and harassing her, and has won a civil protection order against him. As reported by The Daily Beast, Nuzzi’s complaint is not only that her fiancé released material showing her sexting with Kennedy, but that he originally threatened to do so in order to win her back into a relationship with him: and then punished her when she refused to “return.”

The move is typical of the female modus operandi: rather than take responsibility for what she did wrong, she turned the incident into a story of her victimization by a possessive ex-lover who sought to coerce her compliance. The actions that led to her being placed on leave from the New York magazine are conveniently eclipsed by those of an allegedly abusive man. He, in turn, formerly the wronged lover, is now framed as a threat serious enough to require legal restraint.

He has also been placed on a leave of absence from his paper, Politico; it is difficult to believe that, if the sex roles were reversed, a woman who exposed her former fiancé’s sexual misconduct would have been so punished.

It’s a sordid tale all around with no self-evident victim to defend. Perhaps the only victim is, indeed, public confidence, but not for the reasons mentioned.

I, for one, have lost confidence in the ability of public institutions to deal with unscrupulous women like Nuzzi, who refuse to play by recognized rules of professional conduct and then escape censure because of feminist double standards, whereby women’s sexual license must never be constrained, and male discomfort, where it exists, is dismissed.

Having grown up in the sex-permissive era of the 1970s, I am not entirely clear where the moral line should be drawn. Men and women are going to be sexually attracted to one another in the public sphere, and often to act on it. Such sexual attraction is as often the basis for what is good in our societies (appreciation of sexual beauty, benign flirtations, male-female artistic and other collaborations, love, marriage, childrearing) as of what is bad (betrayal, home-wrecking, dishonesty, sexual cruelty, lecherous indifference). Feminists tell us that only women can decide, on a case-by-case basis (and after the fact, if they choose) how and where misconduct occurs; many of us have seen the atrocious #MeToo-style injustices that result when women demand punishments based on their feelings.

I’d like a line that applies to both men and women while taking into account that men and women sometimes interpret interactions differently. But such would require, amongst other discussions, clear talk about female as well as male responsibilities for sexual conduct. It would also require honesty about the destructiveness not only of male sexual aggression (already abundantly addressed) but also of some women’s lack of decent self-restraint. The latter talk will likely remain in short supply.

Excellent piece Janice.

Confession. I had read about her sending the sexual images to RFK and her persistence in continuing that practice. I didn't really think that much of it....until I read your suggestion that we reverse the sexes and consider what we would think of a man who had done something similar. Bingo! I woke up. If a man had done the same thing I would have seen it as badly intrusive, in very poor taste and bordering on abusive. But when I thought of the woman doing this it didn't register as that! I had to laugh at myself and admit that my own gynocentrism was the filter that had caused such a double standard. Gynocentrism runs silent, and it runs deep.

Holding women accountable goes against our gynocentric default. We need to practice, practice, practice holding women accountable!

Thanks for the wake up call Janice!

“Schrödinger’ s feminist” both empowered and victim simultaneously until something happens and she chooses which state offers the most benefit.