The effects of the MeToo movement are ongoing. In March of 2023, author Stephen Elliott settled a defamation lawsuit against the woman who was responsible for his years-long ordeal as an accused rapist. Journalist Moira Donegan had created the Shitty Media Men list, where women could anonymously name men, recounting in as much detail as they wanted the heinous (or trivial) acts the men had allegedly committed. As it circulated in the first 12 hours, the list came to include more than 70 men. Unable to produce any evidence to justify Elliott’s naming, Donegan settled with him for an undisclosed six-figure sum. Speaking to Quillette magazine, Elliott called the list “a false accusation machine” that was “inherently evil.” As we’ll see, Donegan seems unrepentant.

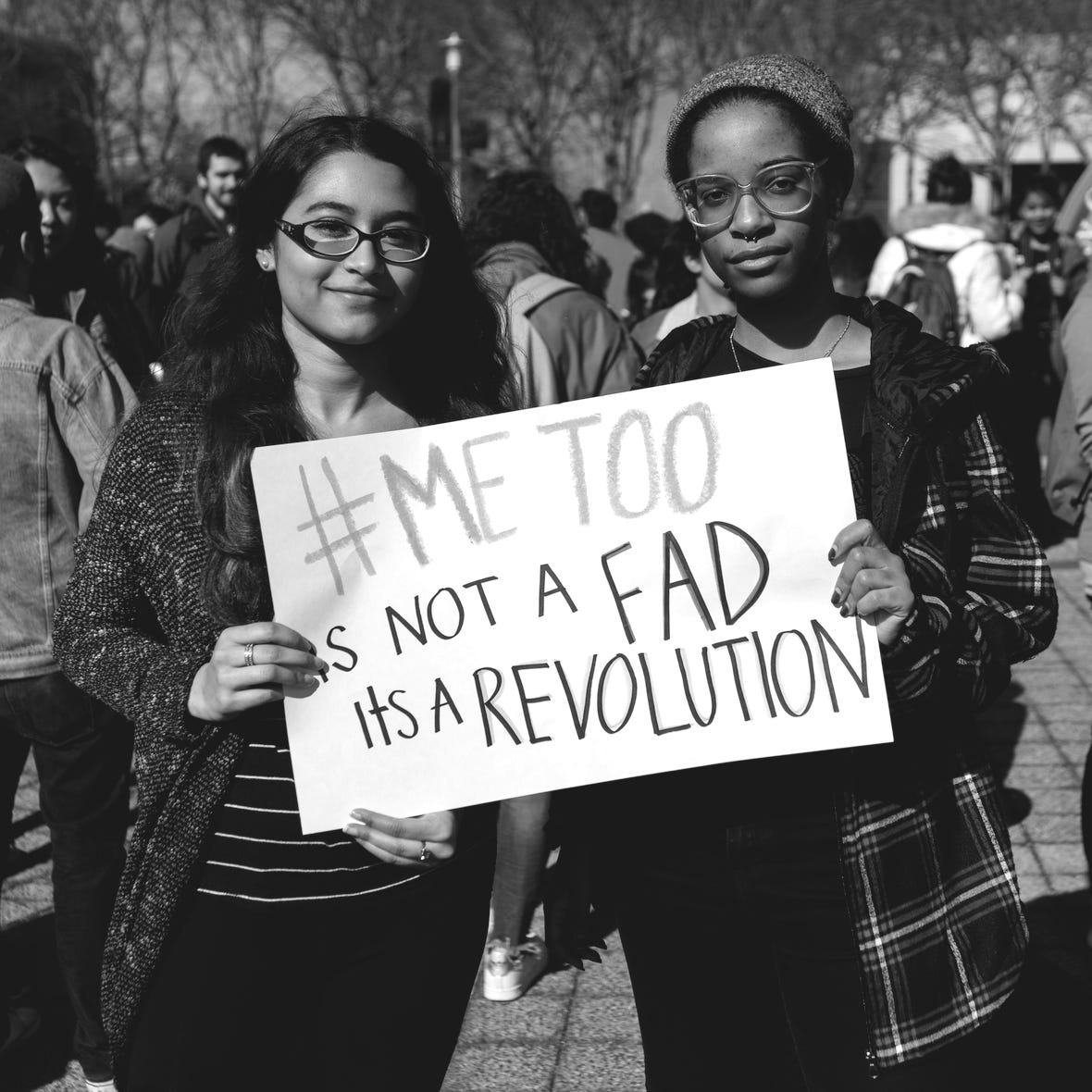

Ostensibly designed to raise awareness of women’s suffering and of the need to address sexual harassment and assault, the MeToo movement was always remarkable for its blithe indifference (or even overt opposition) to bedrock features of free societies such as the presumption of innocence and due process. It turned out that thousands of women (and men) were more than willing to see accused men disgraced, fired from their jobs, excluded from their societies, and dead (by their own hand or from the shock) on the basis of unproven and sometimes anonymous allegations. Hysterical claims, poison-pen letters, salacious exposés, abuser hit lists, and much personal grandstanding quickly became standard features of MeToo, and were allowed to take place, even cheered on, with the rationale that they constituted a salutary public airing of what had remained unspoken from a time not so long ago when rape victims were shamed and suffered alone.

Almost no one pointed out the obvious: that women had been speaking publicly about men’s sexual misconduct for at least 30 years, certainly from the time of Anita Hill’s claims against Justice Clarence Thomas in 1991, and even from the late 1970s as a result of aggressive feminist calls to action like Susan Brownmiller’s Against Our Will (1975) and Catharine MacKinnon’s Sexual Harassment of Working Women (1979). Evidence-free accusations were already common and taken seriously, as can be seen in the treatment of the Duke Lacrosse players, Paul Nungesser, Peter Joyce, Patrick Graham, Mustafa Ururyar, and Mark Pearson (to name only a few). There was no reason for complainants to feel alone. Organizations run by both women and men testified to the seriousness with which sexual assault was regarded, with tributes paid to the alleged “courage” of “survivors.”

Just how many men were caught up in MeToo’s capacious net will never be known. Vox magazine published a list of the high-profile casualties, updated until 2020, that ran to 262 celebrities, CEOs, and politicians—not all, but the vast majority, male. Most of the claims against them were not tested in court, since the alleged irrelevancy of the justice system was one of MeToo’s founding tenets. Of course, these were only the tip of the iceberg, for most of the men ruined were not powerful public figures but ordinary men who lost their jobs, livelihoods, families, reputations, and peace of mind out of the spotlight. A few typical stories can be found here, here, here, here, here, here, and here, but they don’t begin to present the whole sordid picture.

Yet even amongst critics of MeToo, the standard position has been that MeToo was a good idea only occasionally vulnerable to abuse. The usually-excellent Christina Hoff Sommers called it a potentially “great movement,” a helpful “sexual reckoning,” if its energies were properly channeled. Popular YouTuber Karlyn Borysenko, in a 2020 article for Forbes on “The Dark Side of #MeToo,” still called it a “net positive” that empowered people to “share their stories.” Most accounts of MeToo, full of triumphant clichés, don’t even mention the innocent accused: “The generations-long culture of silence is over,” they intone, “The tide has turned from giving abusers a free pass, to listening to and believing survivors and silence breakers” (“Where the #MeToo movement stands, 5 years after Weinstein allegations came to light”).

From the beginning of MeToo, I was mystified by the generally-accepted view that there was anything healing or helpful about the outpouring of public accusation. Even if it were true that women in the past had not been believed (which, as I’ve argued, hasn’t evidently been the case for decades), why would it be good for men to be ruined without the opportunity to defend themselves? MeToo was helpful only in one narrow sense, that it offered a transparent window onto feminism’s aims and beliefs. In a sane society, it would have signaled the end of any claim feminism could make to stand for equality and human dignity. In both popular and scholarly accounts, feminists have revealed their frank opposition to procedural fairness for men as well as their total indifference to (or exultant satisfaction in) male suffering. As the popular saying goes, when people tell us who they are, we should believe them. Two representative examples follow.

A 2018 article by Moira Donegan, afore-mentioned author of one of the better known hit lists that circulated in the fall of 2017, demonstrates the spirit of MeToo in its defiant self-pity. Describing herself as a feminist animated by desire “for a kinder, more respectful, and more equitable world” (unless, that is, you’re an accused man!), Donegan wrote (in “I Started the Media Men List”) of her pride in all the women who contributed anonymous accusations, confident that their motivation was not malice but rather female “power” and “justice.” Though she openly acknowledged that some of the men on the list may not have done what they stood accused of, she did not apologize to them or expresses regret about the devastating consequences they experienced. Her only regret was for her own vulnerability and victimization. “I still don’t know what kind of future awaits me,” she confides near the end of the article, “now that I’ve stopped hiding.”

Spoiler alert: she seems to have landed on her feet. In the same month that she settled the lawsuit with Stephen Elliott, she joined the prestigious Clayman Institute at Stanford University as writer in residence. The announcement of her new gig lauded her as a “leading feminist writer and critic.”

If the media men article is any indication, unfortunately, Donegan won’t be able to model sincerity or coherence for her students. She claims that the document she created, a Google spreadsheet of “rumors and allegations of sexual misconduct,” “was meant to be private.” But she never explains, even in a cursory manner, what steps she took to keep it private. Even a complete naif knows that any document with explosive content shared amongst a large number of people without any mechanism to restrict access is not likely to remain out of the public eye.

Similarly, Donegan’s defense that the spreadsheet “was intended specifically not to inflict consequences, not to be a weapon” is nonsense for at least two reasons. Given that the spreadsheet was a collective effort, Donegan cannot possibly know the intentions of her collaborators; and there is no world today in which the perception that a man is a rapist could not be considered a consequence.

Donegan writes that she took the possibility of false allegations seriously by adding a disclaimer to the list reminding readers to be skeptical. She alleges that she and other women worked on the “radical” assumption that women “can think and judge and choose for ourselves what to believe and what not to.” But wait, aren’t we supposed to “believe women”? Moreover, proper judgement is impossible without fact-checking, cross-examination, counter-testimony. Donegan’s own credulousness is obvious. She boasts that the spreadsheet “did not ask how women responded to men’s inappropriate behavior; it did not ask what you were wearing or whether you’d had anything to drink. Instead, the spreadsheet made a presumption that is still seen as radical: That it is men, not women, who are responsible for men’s sexual misconduct.” Here is a classic instance of feminist question-begging. Of course it is men who are responsible for their sexual misconduct—if it is actually men’s sexual misconduct. Trying to have a rational argument with Donegan must be like pinning jello to the wall.

Along with the vast majority of MeToo defenders, Donegan falls back on the truism that “all available information [she provides none] suggests that false allegations are rare.” Repeating a myth, however, doesn’t make it true, and the simple fact is that Donegan has no idea how many rape allegations are generally false (for the best explanation of why current numbers are useless in estimating false allegations, see William Collins here)—and she certainly doesn’t know how many on her list were. Her guilty conscience on that score is suggested in her waffling justification that “it’s impossible to deny the extent and severity of the sexual harassment problem in media if you believe even a quarter of the claims made on the spreadsheet. For my part, I believe significantly more than that.”

What is significantly more than one quarter? One half? Three quarters? By her own vague admission, then, Donegan does not believe 100% of the allegations, and perhaps believes only about half or three-quarters. If we take the generous estimate of three-quarters, that would mean that 25% of the men named in her spreadsheet were lied about, a possibility that Donegan simply sidesteps. She even professes to believe what no serious mind could entertain: that in the rush of vindictive power, honesty predominated: “Watching the cells populate,” she exults, “it rapidly became clear that many of us had weathered more than we had been willing to admit to one another. There was the sense that the capacity for honesty, long suppressed, had finally been unleashed.” Right-o!

At times in the article, Donegan waxes melodramatic, as when recounting that her supporters “feared that I would be threatened, stalked, raped, or killed.” At other times, she is unintentionally funny, admitting that an added “toll of sexual harassment” is that “It can make you spend hours dissecting the psychology of the kind of men who do not think about your interiority much at all.” But what she never is is sober, fact-based, responsible, or self-critical. Anyone who thinks that women are more empathetic than men should read a few paragraphs of Donegan.

The situation is no more objective or fair-minded on the academic side. In a lengthy essay for the American University Journal of Gender, Social Policy, and the Law, Dr. JoAnne Sweeny (“The #MeToo Movement in Comparative Perspective,” 2020) admitted that MeToo was primarily a publicity stunt, but celebrated it anyway. Men needed to be named, she notes, not because their crimes cried out for justice (many such crimes were not reported to the police) but because naming them brought sustained media attention to feminist claims. “The naming of powerful offenders [sic] and the resulting public disapproval,” writes Sweeny, “was a very important development for the #MeToo movement. By naming these powerful men, the women telling their stories all but ensured that the media would continue investigating [sic] and reporting their allegations, thereby keeping the story in the public eye and giving the movement momentum” (p. 40).

The statement—and the whole laudatory article, which examines MeToo in the U.S., Finland, Portugal, and Germany—is remarkable not only for its honesty about MeToo’s purpose (media exposure and “momentum”) but also for the author’s seeming failure to appreciate—or certainly to rationally defend—the radical philosophy she has adopted, in which unjustly ruined lives are acceptable collateral damage if they support an approved cause. Note how, in the passage just quoted, accused men are called “offenders” rather than “accused,” despite the fact that in the majority of MeToo cases, as Sweeny well knows, accusations were not supported with anything more than an unverified story. Note too the linguistic minimizing of the harms men suffered, in which job loss, reputational destruction, despair, illness, and death are sanitized as “public disapproval.” Perhaps we should not be shocked to discover that Sweeny is a Professor of Law in the Louis D. Brandeis School of Law at the University of Louisville.

Legal concerns about fairness, commensurateness, truth, evidence, and protection against defamation are not a concern of this alleged expert in law. Instead, Sweeny rehearses feminist tenets without critical scrutiny. She accepts that institutional legal avenues have failed women so fundamentally that measures such as public hit lists are justified; she regrets that United States Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanagh was confirmed, allegedly suffering nothing more than some delays and “emotional testimony” in his confirmation hearings; she laments that criminal charges against some high-profile actors were dropped in the wake of MeToo (without explaining why they were dropped); and she expresses frustration that some accused men, including comedian Aziz Ansari (publicly outed as nothing more than a bad date), were able to repair their damaged careers (pp. 43-44). She does not credit claims that MeToo likely increased false allegations, and she is critical of the Trump administration’s decision to reform college policies to protect the rights of accused men (p. 47). In what might be the most remarkable moment in an article approving the evisceration of men’s rights, she expresses scorn that anyone at all is concerned about the effect of false allegations, sarcastically calling such a phenomenon “himpathy” (p. 50).

Sweeny ends her section on MeToo in the U.S. by conveying chagrin that MeToo’s massive assault on men’s due process rights faced “backlash” and that a few men successfully sued false accusers in defamation lawsuits (p. 51). In Sweeny’s moral universe, it seems, a man who is defamed should simply accept his ruined life for the good of the movement (she had previously published an article in Salon magazine [“Can you be sued for sharing your #MeToo story?”] that sympathized entirely with accusers and reassured them that “Proving defamation is difficult”). Despite noting the successes of MeToo in the many men who were “fired, lost elections, were removed from projects, or voluntarily resigned and left the public spotlight” (p. 40), Sweeny concludes her article by stressing the obstacles that remain in the form of an “ingrained patriarchy that withstands efforts at reform” [sic] (p. 87). When such matters as the presumption of innocence and the right to cross-examine one’s accuser are dismissed as irritating remnants of patriarchy, we can see that even the pretense to uphold legal standards has been abandoned.

It is well worth reading these authors and the many other defenders of MeToo, taking them at their word. They are as interesting for what they don’t say as for what they do. In this case, neither MeToo supporter says that MeToo went too far. Neither expresses any regret (even perfunctory) for those it harmed. On the contrary, they emphasize that the MeToo movement didn’t go nearly as far as they would have liked, was a first step only on the long road to women’s justice. And they are clear about what women’s justice is: the stripping of men’s legal rights and the enshrining of a woman’s word as the ultimate power to determine men’s fates.

For those of us who care about justice for all, there can no longer be any doubt about the catastrophic destruction feminism seeks.

Thank you for documenting all of these, Janice. MeToo and BelieveAllWomen destroyed innocent until proven guilty. Almost none of the false accusers and defamatory “journalists” have been punished for ruining lives and livelihoods, which allows them to keep up the hysterias and does a disservice to real victims.

The 2006 Duke Lacrosse scandal is ground zero of this toxicity. I will be publishing a deep dive on Sunday naming and shaming the district attorney, propagandists, and academics responsible for that fiasco.

Good afternoon from New York and thank you Janice for keeping it fresh.

I am an investigative reporter specializing in fraud. Early in the #me2 movement, I wrote a series of articles culminating with a kind of review, "Take a Step Back." There was immediate retaliation from local women claiming to be feminists, who sought to get me fired from all of my freelance jobs. Here is the allegedly offending article:

https://planetwaves.net/take-a-step-back/

My "accusers" called me out on my heinous misconduct: alleged consensual sex 22 years earlier, asking to pet a dog, making women uncomfortable with my writing, and allegedly stating that I was polyamorous at a cocktail party. Here is a summary of what happened.

https://planetwaves.net/me-too-review-the-johnny-depp-verdict/

My total revenue loss was about $50,000 a year in freelance revenue — but I kept my business, which is a kind of astrology news service ( and a journalism nonprofit). If you read my stuff here and would like to support my continuing work, you're most invited to subscribe to my substack. Janice Fiamengo advocated for me at the time, and is also my friend and subscriber (we are both perpetual English majors).

SUBSTACK FOR ASTROLOGY NEWS SERVICE

https://planetwaves.substack.com/

SUBSTACK FOR MY RADIO PROGRAM AND JOURNALISM NONPROFIT

https://planetwavesfm.substack.com/

If you would like to see how one of these things shakes out when properly investigated, here ya go. By far the best document is a confession by one of the "organizers that this was a sham, scam and shonda:

https://planetwaves.net/pdf/191218-wojehowski-final.pdf

JANICE THANK YOU FOR ALL YOU'VE HELPED ME WITH OVER THE YEARS, including tomorrow's forthcoming interview with you and Tom Gold, MEN ARE GOOD.

Yes most of us do our best

with love

Eric Francis Coppolino